In the quiet corners of Chinese homes, in the measured hands of collectors, and within the velvet-lined cases of connoisseurs, there exists a humble yet profound object of fascination: the antique walnut. These are not the common walnuts destined for the kitchen table, but rather specific, carefully selected nuts from wild walnut trees, primarily the species Juglans hopeiensis and Juglans mandshurica, which through years, sometimes decades, of intimate human handling, transform into lustrous, deep-toned artifacts known as wenwan hetao or cultural play walnuts. To the uninitiated foreign observer, they might appear as mere polished nuts, but within Chinese culture, they represent a miniature universe of aesthetic pursuit, philosophical contemplation, and silent historical dialogue. This practice, rooted in antiquity, intertwines the natural world with human culture, creating objects that are both tactilely pleasing and richly symbolic, offering a unique window into a less hurried aspect of Chinese tradition.

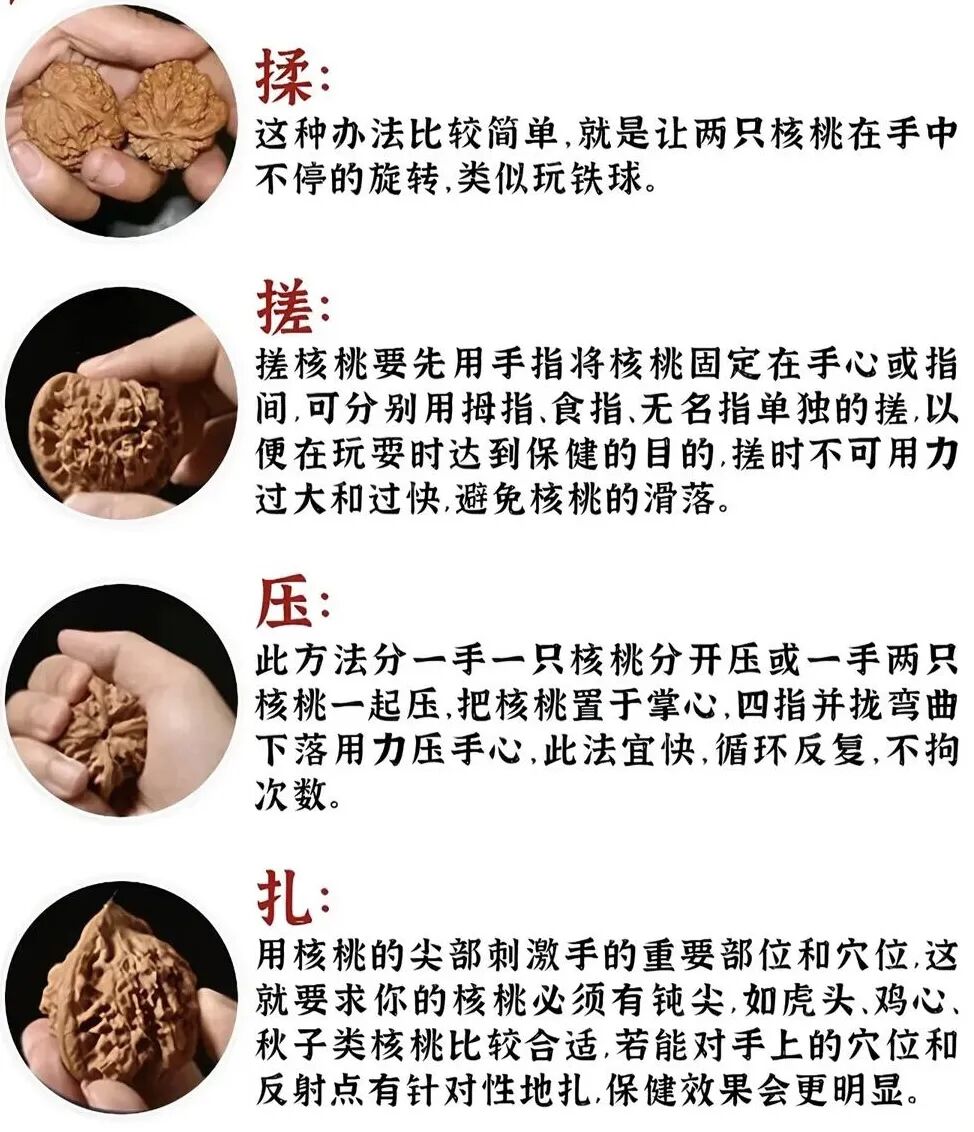

The origins of walnut collecting and appreciation in China are veiled in the mists of time, with most historians tracing its nascent forms to the Sui and Tang dynasties, over a millennium ago. It is believed to have begun among the imperial court and scholarly elite, individuals with the leisure and inclination to seek refinement in everyday objects. Early records and poetic allusions suggest that these hard-shelled fruits were initially valued for their supposed health benefits; the constant, gentle rotation of two walnuts in one palm was thought to stimulate acupuncture points, improving blood circulation and dexterity. This medicinal rationale, however, soon blossomed into an aesthetic and spiritual practice. By the Ming and Qing dynasties, the culture of wan hetao (playing walnuts) had firmly established itself as a respected pastime for literati, officials, and later, wealthy merchants. It became part of the broader wenwan culture, which encompasses the appreciation of scholarly objects like brushes, inkstones, seals, and strange rocks, all reflecting a Confucian-inspired ideal of self-cultivation through quiet engagement with art and nature. The walnut, in its perfect, self-contained form, offered a portable piece of nature that could be shaped and glorified by human touch.

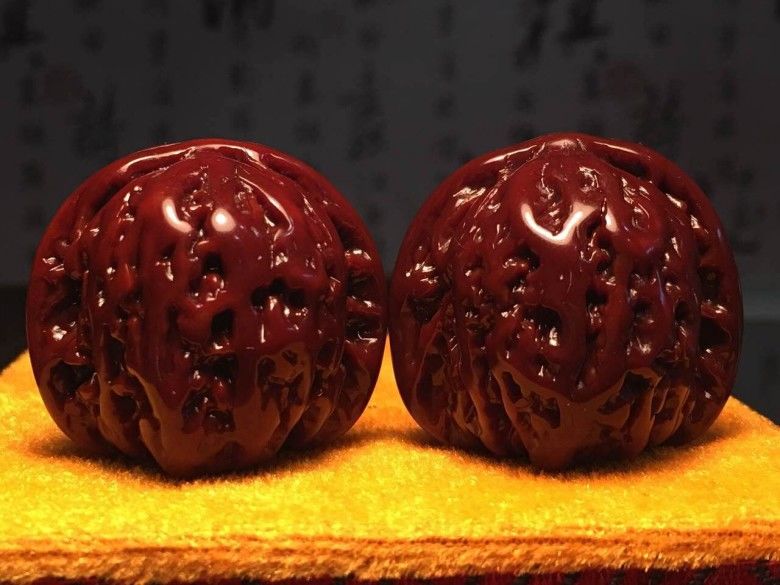

At the heart of this practice lies a deep-seated cultural philosophy that resonates with Daoist and Buddhist principles. The walnut, in its natural state, is a symbol of potential and longevity. Its hard shell protects the life within, mirroring the Chinese philosophical concept of inner strength and resilience. The process of transforming a raw, textured nut into a smooth, glowing artifact is not one of forceful carving, but of patient, persistent nurturing. Collectors speak of panwan, meaning to rotate or polish through handling. This is a meditative, almost ritualistic act. For hours each day, a pair of walnuts is rolled in the hand, the friction of skin against shell gradually wearing down its ridges, deepening its color from a pale brown to rich shades of amber, crimson, and eventually a deep, translucent mahogany akin to jade or antique lacquer. This transformation is seen as a metaphor for personal cultivation—the slow, steady refinement of one’s character through consistent effort and contemplation. The walnut becomes a companion in thought, a tactile focus for the mind, its evolving beauty a direct result of time and dedicated attention, thus embodying the virtue of patience so cherished in traditional Chinese thought.

The selection of the walnuts themselves is an art form requiring a discerning eye. Not every walnut is suitable. The most prized specimens come from old, wild trees in mountainous regions of northern China, such as Hebei, Beijing, Tianjin, and Shanxi. These wild nuts are valued for their dense, thick shells and unique, often irregular shapes. Connoisseurs classify walnuts based on a complex vocabulary describing their form: shizi tou (lion’s head) with dense, bumpy protrusions; guanmao (official’s hat) with a broad, flat top; jigong (cock’s heart) with a pointed tip; and mianhua (cotton) for an exceptionally smooth surface. The ideal pair is not a factory-made duplicate but two nuts that are naturally complementary in size, shape, and texture, forming a harmonious duo. The sound they make when rotated together—a soft, clicking whisper—is also part of their charm. The pursuit of a perfect pair can take years, and historically, exceptional pairs were recorded in catalogs and commanded prices rivaling fine jade. The natural imperfections, the unique veins, and the subtle asymmetry are not flaws but celebrated features, echoing the Chinese artistic appreciation for the beauty of the natural and the imperfect, a concept known as ziran.

The journey from a raw, newly harvested walnut to a cherished antique involves a meticulous and lengthy process. After harvest, the fresh nuts, still encased in their thick green husks, are carefully extracted and cleaned. They are then left to dry slowly and naturally for months, sometimes years, to prevent cracking—a fate that renders a walnut worthless. Once stable, they enter the hands of their owner for the daily ritual of panwan. This is often accompanied by occasional brushing with soft brushes to clean dust from the intricate crevices. Some enthusiasts use natural oils from the human forehead or specialized plant oils to enhance the luster, but purists believe only the natural oils from the hand should be used. Over years, the shell undergoes a chemical and physical change. The surface becomes so smooth it feels like warm jade, and the color deepens into a patina that no artificial means can replicate. This patina, known as baojiang, is the ultimate sign of quality and age, a visual record of every moment it has spent in human care. An antique walnut with a century of such history is not merely an object; it is a repository of time, its sheen holding the memories of generations of handlers.

Beyond individual play, walnut collecting evolved into a sophisticated social and cultural phenomenon. During the Qing dynasty, especially in Beijing, it became common to see gentlemen strolling through markets or sipping tea in taverns, thoughtfully rotating their walnuts. Teahouses and antique markets often served as hubs for collectors to gather, compare treasures, discuss the merits of different shapes, and trade. Knowledge about walnut varieties, ages, and provenance was a mark of erudition and taste. The walnuts were often housed in exquisite small boxes made of zitan or huanghuali rosewood, and displayed alongside other wenwan objects. They were given as prestigious gifts, symbolizing wishes for health, wisdom, and a refined life. In a sense, these small objects facilitated a silent language among peers, communicating status, aesthetic sensibility, and personal temperament. Their value was never purely monetary; it was cultural, emotional, and historical. A pair passed down through a family carried with it the legacy of ancestors, their physical touch preserved in the shell’s glow.

The 20th century, with its wars and cultural upheavals, posed significant challenges to this delicate tradition. During periods of social turmoil, such practices were often dismissed as feudal or bourgeois extravagances. Many precious collections were lost or destroyed. However, like the resilient shell of the walnut itself, the tradition survived in quiet pockets, preserved by dedicated individuals. Since the late 20th century and into the 21st, there has been a remarkable revival of interest in wenwan culture across China, fueled by economic growth, a renewed appreciation for traditional heritage, and a search for meaningful leisure in a fast-paced modern world. The antique walnut market has boomed. While genuine antique pairs from the Qing or early Republican era are rare museum pieces fetching astronomical sums at auction, a vibrant market exists for contemporary nuts from prized old trees. Nurseries now cultivate these specific walnut trees, though wild nuts remain the most coveted. The modern collector demographic has also expanded beyond the elderly to include young professionals seeking a tangible connection to tradition and a mindful escape from digital saturation.

For the international audience, the world of Chinese antique walnuts presents a fascinating case study in the intersection of art, nature, and mindfulness. It challenges Western paradigms of art collection, where value is often tied to an artist’s fame or explicit artistic intervention. Here, the primary artist is time itself, assisted by the anonymous, patient hand of the collector. The artwork is never truly finished; it continues to evolve as long as it is handled. This concept resonates with global trends in mindfulness and sustainable, experience-based hobbies. Foreign collectors and museums are increasingly taking note. Exhibitions on Chinese scholar’s artifacts in institutions abroad sometimes feature these walnuts, explaining their cultural context. To a foreign holder, the walnut offers a uniquely intimate artifact. It requires no battery, no screen, and no instruction manual—only time and touch. Its appeal is universal: the pleasure of a smooth, warm object in the hand, the satisfaction of watching something mature through care, and the silent story it carries from a distant culture. It is a meditation tool, a piece of natural sculpture, and a historical relic all in one.

The sound of two antique walnuts clicking together is a soft, persistent whisper—a whisper of history, of patience, of a cultural dialogue between humanity and nature. In an era dominated by the mass-produced and the ephemeral, these small, time-saturated objects stand as quiet testaments to a different set of values. They represent an appreciation for slow processes, for the beauty inherent in natural forms, and for the idea that the most meaningful transformations often occur through sustained, gentle attention rather than forceful action. The Chinese antique walnut, therefore, is far more than a curio. It is a philosophical object, a vessel for contemplation, and a tangible link to a rich cultural ethos that finds profound meaning in the cultivation of both objects and the self. As they continue to circulate from hand to hand, across generations and now across borders, these whispering shells carry with them an enduring message about the art of patience and the deep, quiet joy of connecting with the past through the simple, profound act of touch.