To the uninitiated, the idea of communal bathing might evoke simple utility—a place to get clean. However, for the people of Northeast China, particularly in provinces like Liaoning, Jilin, and Heilongjiang, the bathhouse represents something far more profound: a cornerstone of community life, a sanctuary for relaxation, and the home of a revered ritual known as the “scrub.” For an outsider, witnessing the vibrant, sprawling complexes dedicated to bathing or experiencing the vigorous, meticulous exfoliation administered by a professional scrub master can be both a cultural revelation and a deeply personal journey into a unique philosophy of wellness and social bonding. This tradition, born from historical necessity and refined into a cultural art form, offers a window into the heart of a region where warmth is cultivated against the cold, both meteorological and metaphorical.

The roots of this deep-seated bathing culture are firmly planted in the region's harsh climate and industrial history. Northeast China endures long, bitterly cold winters where temperatures can plummet far below freezing. Decades ago, when home heating and private hot water supplies were luxuries, the public bathhouse emerged as a vital communal oasis. These spaces, often built and operated by the sprawling state-owned factories that dominated the region's economy, provided a reliably warm refuge. For workers and their families, a trip to the factory-affiliated bathhouse was more than a chore; it was a weekly ritual of warmth and camaraderie. The bathhouse ticket was a standardv benefit, and within the steamy, tiled walls, the hierarchies of the workplace dissolved. Here, people soaked, steamed, and most importantly, scrubbed, forging a sense of shared experience that transcended the industrial routine outside. This historical context transformed a simple act of hygiene into a fundamental social institution, a tradition that has weathered economic changes and continues to thrive in modern, spectacularly evolved forms.

At the core of this institution lies the scrub itself, a practice that elevates bathing from a mere wash to a structured, almost ceremonial cleanse. The process follows a sacred order: one must first wash, then soak in a hot pool to soften the skin, and often follow that with a session in a steamy sauna to “open the pores.” Only then is the body prepared for the main event. The patron lies on a warm, often marble slab, placing their trust in the skilled hands of the scrub master. Using a specialized, slightly abrasive mitt, the practitioner works with a rhythm and pressure that can initially surprise the newcomer. The goal is to generate what is colloquially called “mud”—a greyish roll of dead skin cells, oils, and impurities that are exfoliated from the body. For locals, the sight of this “mud” is a sign of a job well done, tangible proof of a deep clean that leaves the skin glowing. The approach varies by tradition; the robust “Northern style” focuses on thoroughness and strength, while the more nuanced “Southern style” from Yangzhou emphasizes varying pressure along meridians and acupoints, following principles like “eight light and eight heavy touches for eight considerations”. This is often followed by a luxurious “milk rub” or “honey rub,” where the skin is nourished, leaving it extraordinarily smooth. For the first-timer, the sensation ranges from startling to intensely gratifying, culminating in a unique feeling of lightness and renewal that devotees describe as having one’s “soul polished”.

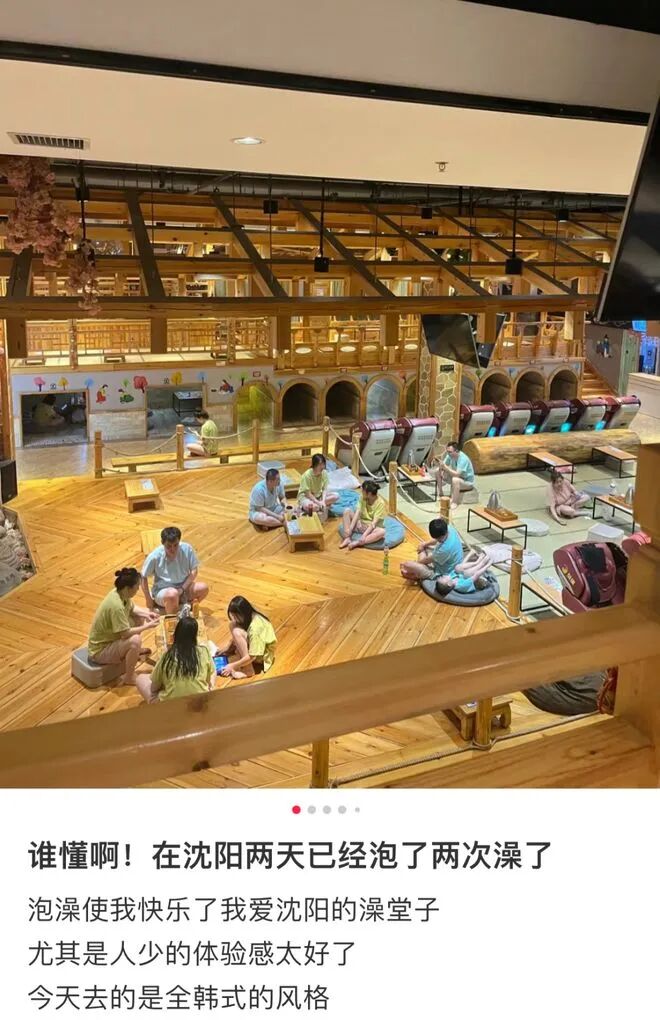

The modern temples where this ritual is performed bear little resemblance to the utilitarian baths of the past. Today’s mega bath complexes in cities like Shenyang are palaces of leisure, redefining the very concept of a spa. They are multi-story wonderlands featuring not just pools and scrub areas, but also gourmet buffets with seafood and steaks, cinemas, karaoke rooms, internet cafes, children’s playgrounds, and serene relaxation lounges where people nap in identical pajamas. For a single entry fee, one can spend an entire day—or even night—enjoying this ecosystem of comfort. It has become a universal social venue: families spend weekends here, friends gather after work, and business associates negotiate deals in a more relaxed atmosphere. The bathhouse, in its contemporary incarnation, fulfills a multifaceted role as a community center, entertainment hub, and culinary destination, all under the pretense of getting clean. This evolution demonstrates the culture’s dynamic nature, adapting to contemporary desires for comprehensive leisure and convenience while preserving the core social and cleansing rituals.

What was once a regional custom has now captured national and international curiosity, fueled in part by social media and viral travel trends. The recent influx of southern Chinese tourists, playfully dubbed “little potatoes” by northeasterners, into cities like Harbin has included an eager pilgrimage to local bathhouses. For many from regions where private showers are the norm, the initial confrontation with communal nudity and the assertive scrub is a profound cultural leap. Stories abound of first-timers being shocked by the intensity or bewildered by the protocols, sometimes leading to humorous misunderstandings. Yet, more often than not, the experience ends in conversion. The journey from apprehension to acceptance, and finally to profound relaxation, is a common narrative. This domestic “bathhouse tourism” has paved the way for growing international interest. Foreign visitors are increasingly seeking out this authentic experience, often guided by the promise of a “deep detox” or the sheer novelty of it. They discover that the ritual offers not just physical cleansing but a temporary shedding of social armor, an equalizing space where everyone is literally and metaphorically laid bare. The industry is rising to meet this new audience, with some establishments offering translation services and guides to the process, formalizing the transmission of this intimate cultural knowledge.

Ultimately, the enduring power of Northeast China’s scrub culture lies in its masterful synthesis of the physical and the social. On one level, it is an unparalleled tactile experience—a vigorous, thorough purification that leaves the body tingling and rejuvenated. On another, far deeper level, it sustains a timeless social ritual. In a world that grows increasingly digital and isolated, the bathhouse remains a fortress of tangible human connection. It is a place where conversations flow as freely as the hot water, where generations mingle, and where the day’s stresses are literally steamed and scrubbed away. It represents a communal investment in well-being, a shared understanding that cleanliness and renewal are not solitary pursuits but can be collective celebrations. From its humble, practical origins in factory towns to its current status as a luxurious and sought-after leisure phenomenon, this culture continues to thrive because it addresses a fundamental human need for both purification and community. To experience it is to understand that in the frosty Northeast of China, true warmth is found not just in the steamy air of the sauna, but in the enduring heat of human connection, meticulously maintained one scrub at a time.