In the tapestry of global demographic trends, China's experience stands out for its speed and scale. The nation, long synonymous with a vast population, is navigating a profound transformation as its birth rate steadily declines. This shift is not merely a statistical curiosity but a fundamental force reshaping the nation's social and economic landscape, moving it from an era of population quantity towards an uncharted chapter focused on population quality .

The figures paint a clear picture. China's population peaked at 1.413 billion in 2021 and has since begun to decrease . In 2023, the country recorded 9.02 million births against 11.1 million deaths, resulting in a natural growth rate of -1.48‰ . While 2024 saw a slight rebound in the birth rate to 6.77‰, the level remains historically low . The total fertility rate (TFR), or the average number of children a woman is expected to have, fell to 1.3 in 2020, placing China in the league of societies with ultra-low fertility rates, a threshold demographers often set at TFR 1.3 or below . This is far less than the replacement level of 2.1 needed to maintain a stable population in the long term . The decline is particularly acute in regions like Northeast China, where provinces consistently record the lowest birth rates in the country, a situation exacerbated by a challenging economic transition and the outmigration of young people . Conversely, regions like Tibet, with a birth rate of 13.87‰ in 2024, and Guangdong, which for five consecutive years saw over a million births, demonstrate that regional economic structures and local cultures create a complex, non-uniform national picture .

Understanding why young people in China are increasingly hesitant to have children requires looking beyond a single cause to a confluence of powerful economic and social pressures. At the heart of the matter lies a formidable economic calculus. The direct cost of raising a child from birth to age 17 is a significant deterrent for many families, especially in major cities where expenses for housing, education, and healthcare are steep . The concentration of high-quality educational resources in urban areas has sparked intense competition, leading to massive investment in extracurricular tutoring and, famously, inflating the cost of "school district housing" . This creates a paradox where economically developed areas, which one might assume are best equipped to support families, often present the highest barriers to parenthood due to these intense cost pressures . Furthermore, the structure of the modern Chinese family adds to the burden. The typical "4-2-1" or "4-2-2" structure, where a young couple is responsible for caring for one or two children and four aging parents, creates a tremendous double pressure that dampens enthusiasm for having more children .

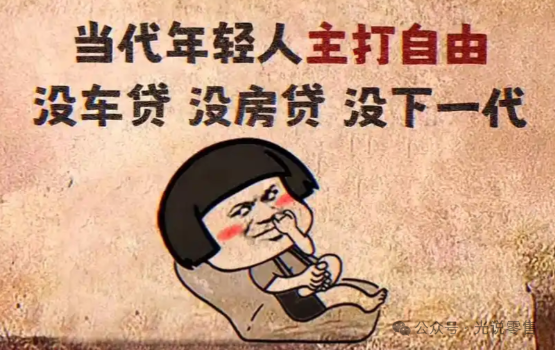

This economic reality is compounded by a deep-seated social transformation. Today's young adults, particularly the post-90s and post-00s generations, hold markedly different views on marriage and family life compared to their predecessors . For them, parenthood has shifted from a familial obligation to a matter of personal choice . Concepts like marrying late, having children later, or remaining child-free are gaining wider acceptance . A survey by the Chinese Academy of Social Sciences found that 37% of young people born after 1995 expressed an unwillingness to take on the responsibility of raising children . This change is closely linked to the advancement of women. With one of the highest female labor force participation rates in the world at 61.5%, Chinese women today contribute significantly to the economy . However, they often face a stark conflict between career aspirations and family responsibilities, a conflict that persistent gender inequalities at home and in the workplace do little to ease . When childcare responsibilities fall predominantly on mothers and paternity leave is limited or insufficiently supported, women bear a disproportionate share of the opportunity cost of having children, which can lead them to delay or forgo parenthood altogether . As one researcher noted, the "childbearing process is often accompanied by interruptions in women's careers," affecting their professional advancement .

Recognizing the long-term challenges, the Chinese government has moved decisively away from its earlier one-child policy. It has enacted a series of major reforms, progressing through the "selective two-child," "universal two-child," and, since 2021, the "three-child" policy framework . These policy shifts represent a fundamental reorientation from managing population size to improving its structure and quality . The supporting measures are extensive. Since 2025, the government has provided an annual childcare subsidy of 3,600 yuan per child until the age of three . Nationwide, most provinces have extended maternity leave by 30 to 90 days, and policies such as tax deductions for childcare expenses have been introduced . Local governments are also experimenting with innovative models, such as Beijing's "community parent-child stations" and Hangzhou's family service centers, aimed at reducing the practical burdens on families . However, as officials acknowledge, the effects of these policies are not immediate. Population reproduction cycles are long, and influencing deeply personal decisions like having children is a complex challenge that requires sustained effort . Some experts also point out that current policies can sometimes lean too heavily on financial subsidies while not adequately addressing the critical need for accessible childcare services and workplace flexibility .

Faced with the difficulty of significantly raising the birth rate in the short term, a compelling perspective is gaining traction, one that shifts the focus from the quantity of people to their quality. Wolfgang Lutz, a leading global demographer, argues that the conventional fear over falling birth rates may be misplaced . He suggests that the traditional metric of the age-dependency ratio, which simply counts the number of working-age people supporting the elderly, is flawed because it ignores the power of human capital . His research introduces the concept of the "education-weighted dependency ratio," which factors in the productivity gains from a more educated populace . The core idea is that a smaller but better-educated workforce can be far more productive and innovative, potentially offsetting the economic drag of an aging population . China has made remarkable strides in this area. By 2024, the average years of schooling for the working-age population had reached 11.21 years, and over half of the women born after 2000 were enrolling in higher education . This vast reservoir of human capital is seen as a new "talent dividend" that can drive growth in technology-intensive industries, a crucial strategy for the future . Therefore, the national strategy of "population quality development" aims to create a virtuous cycle where a highly skilled population drives innovation, which in turn creates higher-value jobs, leading to greater prosperity even with a smaller overall population . This approach dovetails with efforts to tap into the "silver economy," recognizing the growing market of older adults and the potential of older workers as a valuable experienced resource .

China's journey with its declining birth rate is a multifaceted story of a society in rapid evolution. It is a narrative shaped by the weight of economic costs, the empowerment of women, the transformation of personal values, and the strategic pivot of a nation. The decline is a powerful, self-reinforcing trend that will continue to influence China's society and economy for decades to come, presenting challenges such as a shrinking labor force and an increasingly aged population . Yet, it also acts as a catalyst for change, pushing the country to invest in its people, innovate its social policies, and strive for a more balanced development model. The ultimate outcome for China will likely depend less on a dramatic reversal of birth rates and more on its success in fostering a highly skilled, productive population and building a genuinely supportive environment for those who do choose to raise the next generation . The silent transition in its cradle carries echoes that will define China's path forward in the 21st century.