In the ancient streets of Wuhu, a city nestled along the Yangtze River, an unassuming craftsman has become an unexpected internet sensation. Wang Jingyang, known online as the "Dough Figurine Master," spends his days surrounded by colorful clays and curious onlookers. With hands weathered by decades of work, he transforms lumps of inert material into vibrant characters—mythical beasts, cartoon heroes, and whimsical creatures that seem to breathe with personality. His stall, tucked away in the bustling Wuhu Ancient City, has long been a quiet landmark. But recently, it has turned into a pilgrimage site for young travelers clutching phone screens filled with images of their favorite pop culture icons, hoping to see them recreated in dough .

Wang's journey to fame began subtly. A visitor once handed him a picture of a trendy anime character and asked, "Can you make this?" Wang, then in his fifties, had never seen the figure before. Yet, with a few deft moves—kneading, pinching, and carving—he produced a miniature replica so precise it captured even the quirks of the original design. The customer, delighted, shared a video of the process online. Overnight, the clip went viral, amassing millions of views and pulling Wang into the spotlight. Comments flooded in: "This uncle hasn't realized these are his last peaceful days," one user joked. Another wrote, "His face has lost its smile!"—a humorous nod to the sudden demand overwhelming the once-tranquil stall .

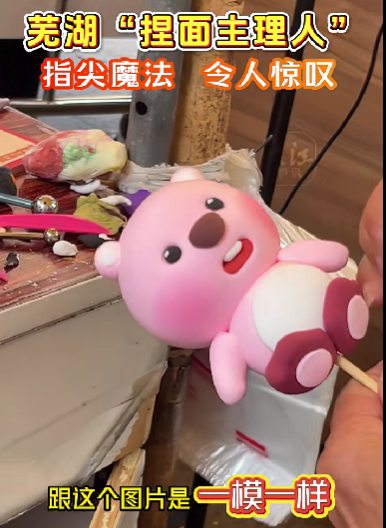

What sets Wang apart is not just skill but adaptability. For over thirty years, he has practiced the ancient craft of miansu, or dough figurine art, which dates back to the Han Dynasty. Traditionally, artisans shaped figures from tinted flour paste, depicting zodiac animals, folklore heroes, or festival symbols. Wang, however, has reimagined the practice. He swapped fragile flour-based dough for durable modeling clay, ensuring his creations withstand time. His subjects evolved, too—from classic Sun Wukongs and pig deities to modern idols like Labubu, Ultraman, and viral "star people." When a customer requested a round-faced, blushing creature, Wang didn't just replicate it; he suggested adding a blue skirt and matching bow to enhance its charm. "Details are the soul of a dough figurine," he explains. Even if a hat covers the ears, he'll sculpt them underneath, refusing to cut corners .

This synergy of tradition and innovation resonates deeply in Wuhu, a city historically known as a commercial hub and cradle of craftsmanship. Here, ironwork paintings, silk lanterns, and lacquerware have flourished for centuries, nurtured by a culture that values diligence and artistry. Wang's story mirrors the city's spirit—humble yet resilient, deeply rooted yet forward-looking. As an article notes, Wuhu has long been a "city of makers," from automakers like Chery to snack brand Three Squirrels. Similarly, Wang's three-decade dedication—"choose one thing, devote a lifetime"—echoes the local ethos of steady perseverance .

The influx of attention hasn't swayed his routine. Wang still arrives at his stall by 9:30 a.m., unpacking tools to the chatter of eager visitors. Some line up as early as 8 a.m., traveling from neighboring Hefei, Nanjing, or as far as Shenzhen. Each piece takes 10 to 30 minutes, and with a daily limit of 20-30 orders, patience is part of the experience. Yet few complain; instead, they document the process on phones, marveling at how a lump of clay morphs into 3D art. One woman waited 90 minutes for a custom gift, passing time by helping Wang package finished pieces. Another visitor, unable to secure a slot, saved the artisan's contact for a future mail-order. "I'm already a Wuhu local," Wang says, smiling. Having moved from northern Jiangsu as a teen, he now considers the city home .

His appeal lies in a rare balance: honoring heritage while embracing change. Younger generations, he realizes, connect not with mythical tales but with digital avatars and blind-box toys. So he studies their references—the toothy grin of Labubu, the stout silhouette of a capybara—mastering them through observation. "At first, I didn't recognize these characters," he admits, "but years of experience help me grasp their essence." An art professor notes that translating 2D images into 3D forms requires exceptional spatial skill, a testament to Wang's mastery .

Yet behind the buzz, Wang remains grounded. He declines to raise prices, avoids overworking, and clocks out by 8:30 p.m. to rest. His son is now learning the craft, hinting at a future where family legacy meets contemporary demand. Recognized as Wuhu's "cultural tourism ambassador," Wang embodies a bridge—linking ancient streets to digital trends, solitary artistry to communal joy .

In a globalized era where fast fashion and digital avatars dominate, the dough figurine master offers something rare: a tangible piece of wonder, shaped by human hands. As visitors depart with their personalized treasures, they carry more than souvenirs; they hold fragments of a living tradition, proof that in Wuhu's ancient lanes, magic still grows from humble beginnings .