Nestled in the folds of the mountains in northern Guangxi, China, Longsheng Multi-Ethnic Autonomous County is like a warm and unpolished jade, hiding the most primitive texture of Guilin's landscapes. Its landform of "nine parts mountains, half part water, and half part farmland" has nurtured the 2,300-year-old Longji Terraced Fields and nourished a cultural secret land where ethnic groups such as the Miao, Yao, Dong, and Zhuang live in harmony.

China's Longji Terraced Fields are the most vivid fingerprints of the earth. The "Seven Stars Accompanying the Moon" in Ping'an Zhuang Terraced Fields is like the Big Dipper falling into the mortal world—seven small fields surrounding a crescent-shaped one. When irrigated in spring, the shimmering water resembles broken mirrors inlaid among the mountains. The "Thousand-Layer Sky Staircase" in Jinkeng Red Yao Terraced Fields is even more magnificent, stretching from 300 meters to 1,100 meters above sea level. During the autumn harvest, the rolling rice waves form golden tides connecting to the sky. The most wonderful scene comes after the first winter snow, when the field ridges outline black-and-white ink wash contours, and occasional torches passing through turn into flowing stars. In 2018, these terraced fields were inscribed on the list of Globally Important Agricultural Heritage Systems, affirming the ecological wisdom of "forests above, fields below".

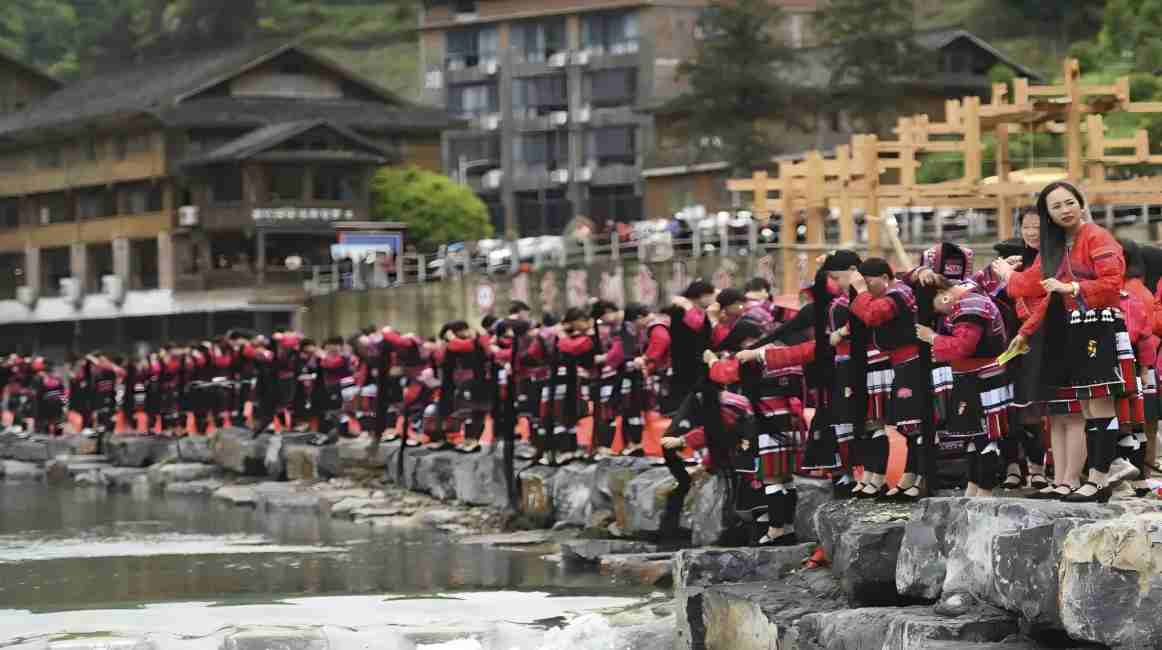

Ethnic customs flow like poetry among the mountains. Long-Haired Yao women in Huangluo Yao Village dress their hair in the morning, with jet-black tresses reaching their ankles. The scene of collective hair washing has become a living intangible cultural heritage landscape, and the coming-of-age ceremony during the annual "Long Hair Festival" is solemn and touching. On the Zhuang's "March 3rd Festival" (Spring Plowing Festival), villagers tug-of-war and sing antiphonal songs in the terraced fields, while the aroma of five-colored glutinous rice—dyed with maple leaves and red-blue grass—lingers over the stilted buildings, holding the natural code of agricultural peoples. The Dong's Wind and Rain Bridge is an architectural miracle, an all-wooden mortise and tenon structure without a single nail or iron piece. The harmony of Dong Grand Choirs often echoes under the corridor, blending with the gurgling stream below.

Longsheng is equally vivid in taste. Hmong oil tea, known as "refreshing soup", is made by boiling old tea beaten in an iron pot with ginger and garlic, then pouring it over fried rice flowers and rice cakes, offering a mix of bitterness, sweetness, fragrance, spiciness, and umami in one bowl. Thin slices of charcoal-smoked preserved pork steamed to perfection complement the bitterness of Longji Tea beautifully. In the lights of the riverside food street in the county town, the steam rising from crispy duck, red glutinous rice, and bamboo shoot hot pot is a testament to the integration of multi-ethnic cuisines.

The county town holds traces of time. Between the black tiles and red walls of Chunan Guan, Huizhou-style architecture contrasts with ethnic carvings. This ancient Qing Dynasty building is now an exhibition hall themed on ethnic unity, with stories of integration hidden in every brick crevice. Climbing Lansheng Tower for a distant view, the Sangjiang River winds around the mountain city like a belt—sea of clouds rolling over the roof ridges during the day, and stars shining in harmony with city lights at night. The glass viewing platform at North Bank Scenic Spot hangs in mid-air, with Miao and Yao totems underfoot and a picture of "city in the mountains, water in the city" before the eyes.

From terraced fields to mountain cities, from the aroma of oil tea to the sound of bronze drums, Longsheng's beauty has never been an isolated scene. When the warmth of hot springs soaks the skin and the luster of chicken blood jade brightens the eyes, this land has always been telling: the symbiosis of nature and humanity is the most touching scenery.