Across China, a quiet yet vibrant revolution is taking place on weekends and holidays, not in sleek digital startups or crowded downtown bars, but in the open air of bustling, sometimes dusty, local markets. The ancient tradition of “going to the fair,” known as Ganji, once the cornerstone of rural commerce and social life, is experiencing an unexpected and vigorous revival. This revival, however, wears a distinctly new face. It is being championed and reshaped not by the older generations who remember its necessity, but by urban youth, who are flocking to these gatherings in growing numbers, transforming them into hubs of contemporary culture, culinary exploration, and a sought-after authenticity in an increasingly homogenized world.

To understand the significance of this trend, one must first step back and consider the historical weight of the fair. For centuries, in villages and towns across China, the fair was more than a market; it was a fundamental rhythm of life. Held on designated days according to the lunar calendar or local custom, it was a temporary nexus where farmers, artisans, and traders would converge. Here, they exchanged goods from the hinterlands—fresh seasonal produce, hand-woven baskets, live poultry, simple pottery, and ironware. It was a place for practical transactions, certainly, but its social function was equally vital. It was a news network, a matchmaking venue, a space for entertainment featuring street performers and storytellers, and a rare chance for scattered communities to connect. The air would be thick with the cacophony of haggling, the calls of vendors, the smells of rustic food, and the palpable energy of collective gathering. As modernization accelerated, with permanent supermarkets and online shopping eroding their practical utility, many such fairs dwindled, fading into memory or persisting in diminished forms, often patronized mainly by an aging population.

The contemporary resurgence defies this narrative of decline. Today, a new wave of young Chinese, predominantly city-dwellers in their twenties and thirties, are seeking out these fairs, often traveling significant distances to the peripheries of cities or into the countryside. Their motivation is a complex tapestry woven from threads of nostalgia, culinary curiosity, aesthetic appreciation, and a deep psychological need for connection and tangibility. In a society defined by breakneck digitalization, the physical, uncurated experience of a fair offers a powerful antidote to virtual overload. For these young explorers, the fair is not about procuring daily necessities but about acquiring an experience. They go not as obligatory shoppers, but as conscious participants in a living heritage.

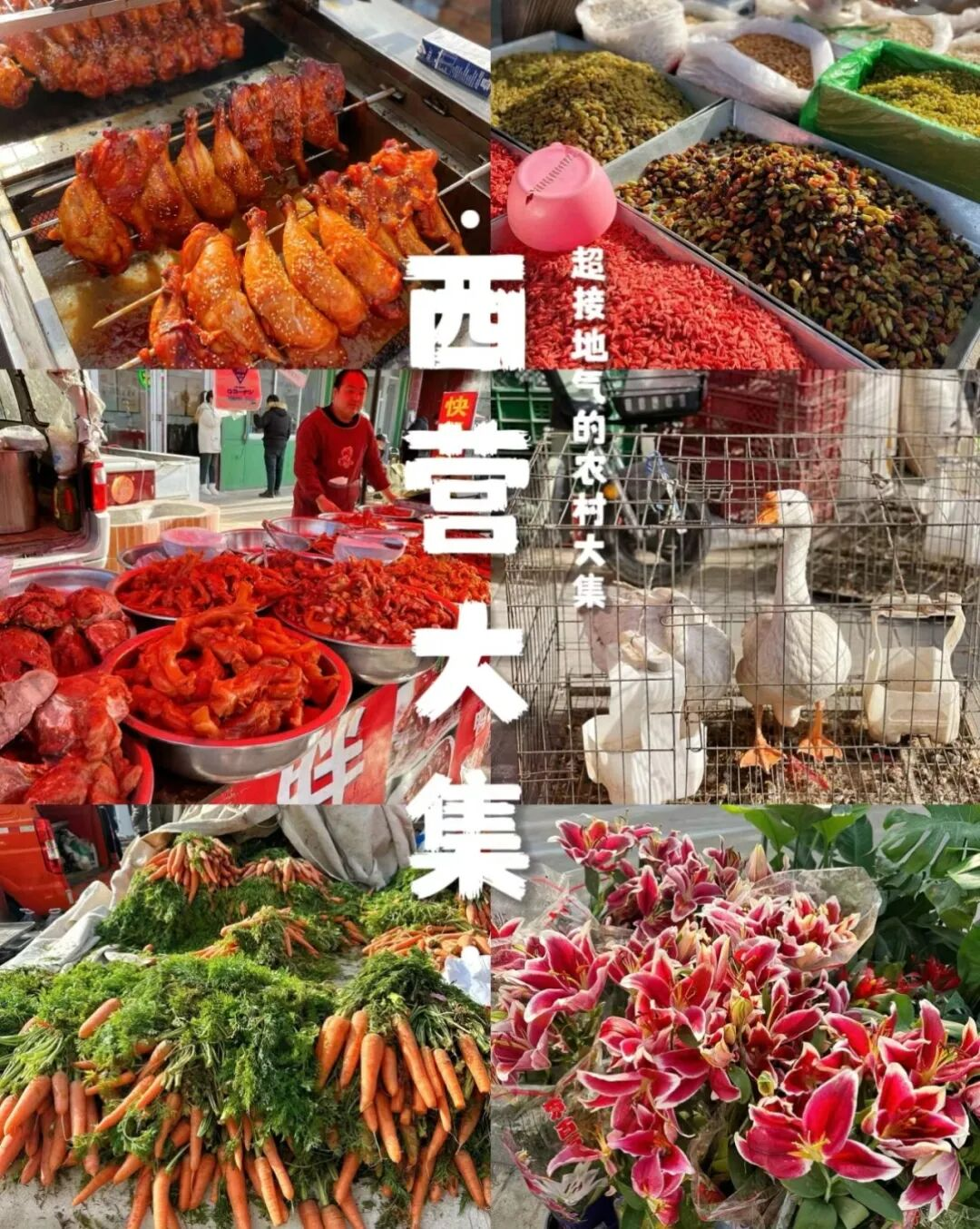

At the heart of this attraction is an intense focus on food, redefining the concept of “farm-to-table.” Young visitors are drawn to the unmediated provenance of the ingredients. They eagerly seek out tomatoes that taste of the sun, eggs from free-ranging chickens, wild-foraged herbs, and artisan-made tofu still warm from the press. This desire goes beyond gourmet trends; it is a quest for trust and transparency in an age of food safety concerns and industrial production. The transaction is personal—they can speak directly to the grower, learn about the harvest, and hear stories of the land. This direct line from producer to consumer fulfills a yearning for authenticity that pre-packaged supermarket goods cannot satisfy. Furthermore, the fairground food stalls have become destinations in themselves. While traditional snacks like jianbing (savory crepes), grilled skewers, and sweet rice cakes remain staples, they are now documented through smartphone lenses, shared on social media platforms like Xiaohongshu (Little Red Book) and Douyin, and reviewed as critically as restaurant meals. The act of eating at the fair is both a sensory pleasure and a performative one, a way to curate and broadcast a lifestyle centered on discovery and “realness.”

Parallel to the culinary journey is an aesthetic and cultural re-engagement. The young crowd exhibits a finely tuned appreciation for craftsmanship. They browse stalls selling hand-thrown pottery, naturally dyed indigo fabrics, delicate bamboo ware, and intricate paper-cuttings not as quaint relics, but as embodiments of mindful living and sustainable choice. These items, often purchased directly from the artisans themselves, carry a narrative. They represent an alternative to mass-produced goods, aligning with growing environmental consciousness and a preference for uniqueness. The fair, in this sense, becomes a platform for preserving traditional crafts by creating a new, economically viable market for them. It empowers local artisans and allows urban youth to connect with material culture in a meaningful way. The aesthetic of the fair—the vibrant chaos, the textured surfaces, the unpolished honesty—is itself a draw, offering a visual and tactile richness starkly different from the minimalist, sterile environments of modern malls.

Social media has been the indispensable engine of this revival. Platforms are flooded with visually appealing content: videos of steam rising from a giant wok, close-ups of textured handicrafts, photos of friends laughing against a backdrop of colorful stalls. These posts are often tagged with locations and recommendations, effectively crowdsourcing a map of the most authentic and interesting fairs across the country. They frame the fair experience as aspirational—a marker of being in-the-know, culturally sensitive, and adventurous. This digital amplification creates a feedback loop; online discovery drives offline visitation, which in turn generates more online content, pulling in ever-larger circles of participants. The fair thus becomes a shared cultural event within digital communities, strengthening its appeal and reach.

Underlying this trend is a profound search for community and psychological grounding. For many young Chinese navigating the pressures of urban life—high costs of living, competitive work environments, and often a sense of social isolation—the fair offers a temporary escape and a dose of communal warmth. Its atmosphere is inherently social, unscripted, and human-scaled. The act of wandering through the crowds, the spontaneous conversations with vendors, the shared enjoyment of food with friends, all foster a sense of belonging and immediacy that can be elusive in the anonymous urban sprawl or behind screens. It is a form of “lightweight” tourism and cultural immersion close to home, offering the satisfactions of travel without the long journey. Psychologically, it represents a conscious slowing down, an engagement with cyclical, seasonal time as opposed to the relentless linear time of productivity and deadlines.

Importantly, the youth are not passive consumers in this revival; they are active co-creators. Their presence and spending power incentivize the preservation and adaptation of the fair format. Some organizers now consciously blend traditional elements with contemporary appeals, perhaps incorporating live folk music, DIY workshop zones, or spaces for young designers to sell their own crafts alongside those of veteran artisans. This fusion ensures the fair remains dynamic and relevant. It is no longer a static museum piece but a living, evolving tradition.

The revival of Ganji among China’s youth is, therefore, a multifaceted phenomenon. It is a culinary movement championing traceable, honest food. It is a cultural renaissance that values heritage craftsmanship and tangible beauty. It is a social media-fueled trend that turns local gathering into national fascination. And, on a deeper level, it is a collective response to the anxieties of modernity—a search for roots, authenticity, and human connection in a fast-changing world. By embracing the fair, these young people are bridging a perceived chasm between urban and rural, past and present. They are not merely visiting history; they are actively rewiring it, infusing an ancient social custom with new meaning and vitality, ensuring that the vibrant, chaotic, and deeply human tradition of the fair continues to thrive in the 21st century. In the laughter of friends sharing a street-food snack, in the careful selection of a handcrafted cup, and in the simple act of wandering through a crowd on a sunny morning, a new chapter of an old story is being joyously written.