The abacus, known in China as the suanpan, stands as a testament to human ingenuity, a simple wooden frame strung with beads that has for centuries encapsulated the mathematical spirit of a civilization. This ancient calculating device, often hailed as the world's oldest computer, is far more than a relic; it is a living tradition that continues to whisper secrets of time-honored wisdom and intellectual elegance . Its story is not merely one of arithmetic but a rich narrative woven into the very fabric of Chinese culture, symbolizing a journey of intellectual pursuit that spans millennia. For over two thousand years, the rhythmic clicking of its beads provided the soundtrack to commerce, science, and daily life, a sound that has only recently been softened by the silent hum of digital technology .

The origins of the Chinese abacus are shrouded in the mists of time, with its conceptual roots tracing back to the Spring and Autumn Period (770-476 BC) . Early methods of calculation involved humble materials like counting rods, small sticks arranged on boards to represent numbers . The earliest known written reference to a bead-based calculation method appears in a 2nd-century AD text by Xu Yue, which documented fourteen different calculation techniques, among which was the precursor to the abacus . This evolutionary path culminated in a recognizable form by the Song Dynasty (960-1279 AD), a period often considered the golden age of the abacus . A clear depiction of the tool can be seen in the famous painting "Riverside Scene at Qingming Festival" by Zhang Zeduan, where an abacus rests on the counter of a bustling medicine shop, a silent witness to the commercial vigor of the era . The device's design was standardized during the Ming Dynasty (1368-1644), as detailed in classical texts, solidifying the form that would be passed down through generations .

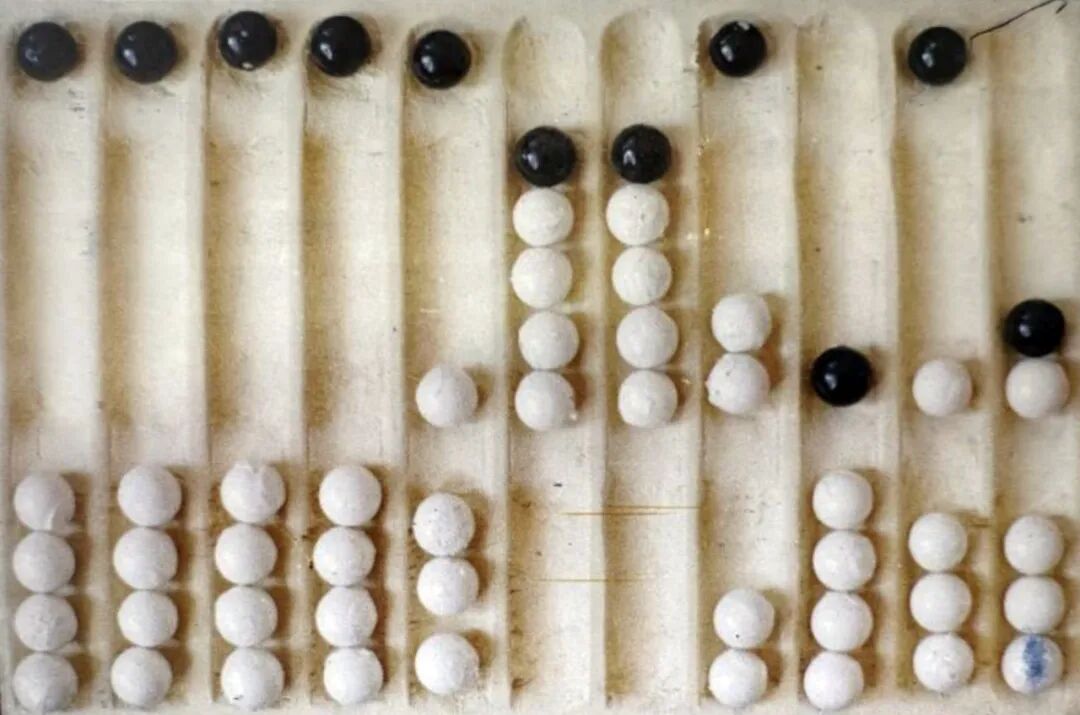

The structure of the traditional Chinese abacus is a marvel of elegant simplicity. It consists of a rectangular wooden frame divided by a horizontal beam, creating an upper section and a lower section . Through this frame pass a series of vertical rods, typically thirteen or more. Each rod holds two beads in the upper deck, traditionally called "Heaven" beads, each representing a value of five. Below the beam, in the "Earth" section, are five beads, each representing a value of one . The rods themselves correspond to place values, starting from the units on the right, then tens, hundreds, thousands, and so on, mirroring the decimal place-value system used in modern numerals . Before any calculation begins, the abacus is cleared, or set to zero, by moving all the upper beads away from the central beam and all the lower beads down away from it . To represent a number, beads are moved towards the beam. For instance, the number seven is formed by moving one Heaven bead (value 5) and two Earth beads (value 1 each) towards the center on the units rod . The operation relies on a "five-plus decimal system," where counting beyond four on a single rod involves using the upper bead, and reaching ten on one rod necessitates carrying over to the next .

The true power of the abacus, however, lies not in its static representation of numbers but in the dynamic art of calculation known as Zhusuan . This practice involves a set of defined rules and oral formulas, often expressed as easy-to-remember rhymes, which guide the movement of beads to perform complex operations with remarkable speed . Addition is performed by directly adding the beads of the second number to those of the first. Subtraction is its reverse. For more intricate operations like multiplication and division, the processes are more elaborate, involving the setting of numbers across different columns and systematic operations across rods . A skilled practitioner can perform these calculations with breathtaking fluidity. Fingers flutter, beads knock gently, and answers emerge within seconds, a performance that rivals the speed of modern electronic calculators for basic arithmetic . This proficiency can be developed to such an extent that it evolves into mental abacus calculation, where the user visualizes an abacus in their mind to perform calculations without the physical tool, a technique known to significantly enhance cognitive abilities like concentration and memory .

The applications of the abacus were once all-encompassing in Chinese society. It was the indispensable engine of commerce, used by merchants for accounting and calculating profits, so much so that it became a cultural symbol of wealth and prosperity . It was a crucial instrument for officials managing state finances and taxation . Its utility extended to advanced scientific fields, where astronomers used it to compute celestial movements and create calendars, and engineers employed it in architectural and hydraulic projects . The abacus was also a cornerstone of education, a required skill for scholars and a fundamental tool for teaching mathematics . The influence of Zhusuan eventually transcended China's borders. During the Ming Dynasty, the work of mathematician Cheng Dawei, whose comprehensive texts systematized abacus calculation methods, reached Japan and other parts of East Asia, profoundly influencing their mathematical traditions and leading to the development of local variants like the Japanese soroban .

With the advent of digital calculators and computers in the late 20th century, the practical utility of the abacus in everyday life and professional settings inevitably declined . It was gradually phased out of school curricula, and the sight of a shopkeeper deftly sliding beads became increasingly rare . Yet, rather than fading into obsolescence, the abacus underwent a remarkable transformation, shifting its primary role from a practical calculator to a cultural treasure and an educational tool. Recognizing its profound significance, China listed Zhusuan as a national-level intangible cultural heritage in 2008 . This effort culminated in its international recognition on December 4, 2013, when UNESCO inscribed it on the Representative List of the Intangible Cultural Heritage of Humanity, cementing its status as a crucial part of humanity's shared intellectual and cultural heritage .

This recognition has spurred a revival of interest. Today, the value of the abacus is increasingly appreciated not for calculation alone but for its cognitive benefits. Schools across China and in other parts of the world have reintroduced abacus training, particularly for young children, as a means to enhance mental arithmetic skills, improve concentration, foster memory, and develop overall cognitive function . Museums dedicated to the abacus, such as the China Abacus Museum in Nantong, have been established to preserve and showcase its history, displaying artifacts ranging from enormous rosewood abacuses to tiny, exquisitely crafted ornamental pieces . Teachers like Wang Suqiu, a representative inheritor of the Cheng Dawei method at a primary school named after the mathematician, are exploring innovative ways to blend traditional Zhusuan approaches with modern mathematics pedagogy, ensuring the ancient skill remains relevant for new generations . The abacus has thus found new life as a tool for brain training and a bridge to cultural identity. It symbolizes wisdom, efficiency, and the enduring power of ancient knowledge . In a world dominated by fleeting digital data, the deliberate, tactile engagement with the beads offers a different kind of wisdom—one of focus, patience, and the deep satisfaction that comes from mastering a complex skill. The story of the Chinese abacus is ultimately one of resilience and adaptation. It is a story that continues to be told, not through the hum of a processor, but through the gentle, persistent click of beads, a sound that connects the present to the accumulated wisdom of countless past generations .