For millennia, the rhythm of life across the vast and varied landscape of China has been guided by a celestial clock, a sophisticated system known as the Twenty-Four Solar Terms. This ancient framework, born from profound observation and deep reverence for the natural world, represents a monumental intellectual achievement. It is not merely a calendar for farmers but a philosophical and cultural cornerstone that encapsulates a holistic understanding of the universe, where heaven, earth, and humanity are inextricably linked. The system divides the solar year into twenty-four equal segments, each marked by a specific term that poetically and precisely describes a corresponding astronomical, climatic, and phenological shift. This intricate knowledge, refined over centuries and officially recognized as a UNESCO Intangible Cultural Heritage, offers a captivating window into the Chinese worldview, one that seeks harmony with the immutable cycles of nature rather than dominance over them.

The origins of the Twenty-Four Solar Terms are as deep-rooted as the oldest oaks in the Yellow River Valley, dating back to the Shang and Zhou dynasties over three thousand years ago. Ancient astronomers, gazing at the star-flecked canvas of the night sky, began to discern patterns. They meticulously recorded the shifting lengths of shadows cast by gnomons, simple yet effective sundials, and charted the consistent movement of the sun. Their groundbreaking discovery was the solar year's cyclical nature, which they mapped onto the ecliptic—the sun's apparent path across the sky—dividing this 360-degree circle into twenty-four sections of fifteen degrees each. The position of the sun at each of these points heralded the beginning of a new solar term. This system was first comprehensively documented in the Han Dynasty around 104 BCE in the Taichu Calendar, a testament to its advanced scientific understanding. The terms were established primarily in the Yellow River basin, the cradle of Chinese civilization, making them a cultural artifact deeply reflective of that specific region's climate and ecology.

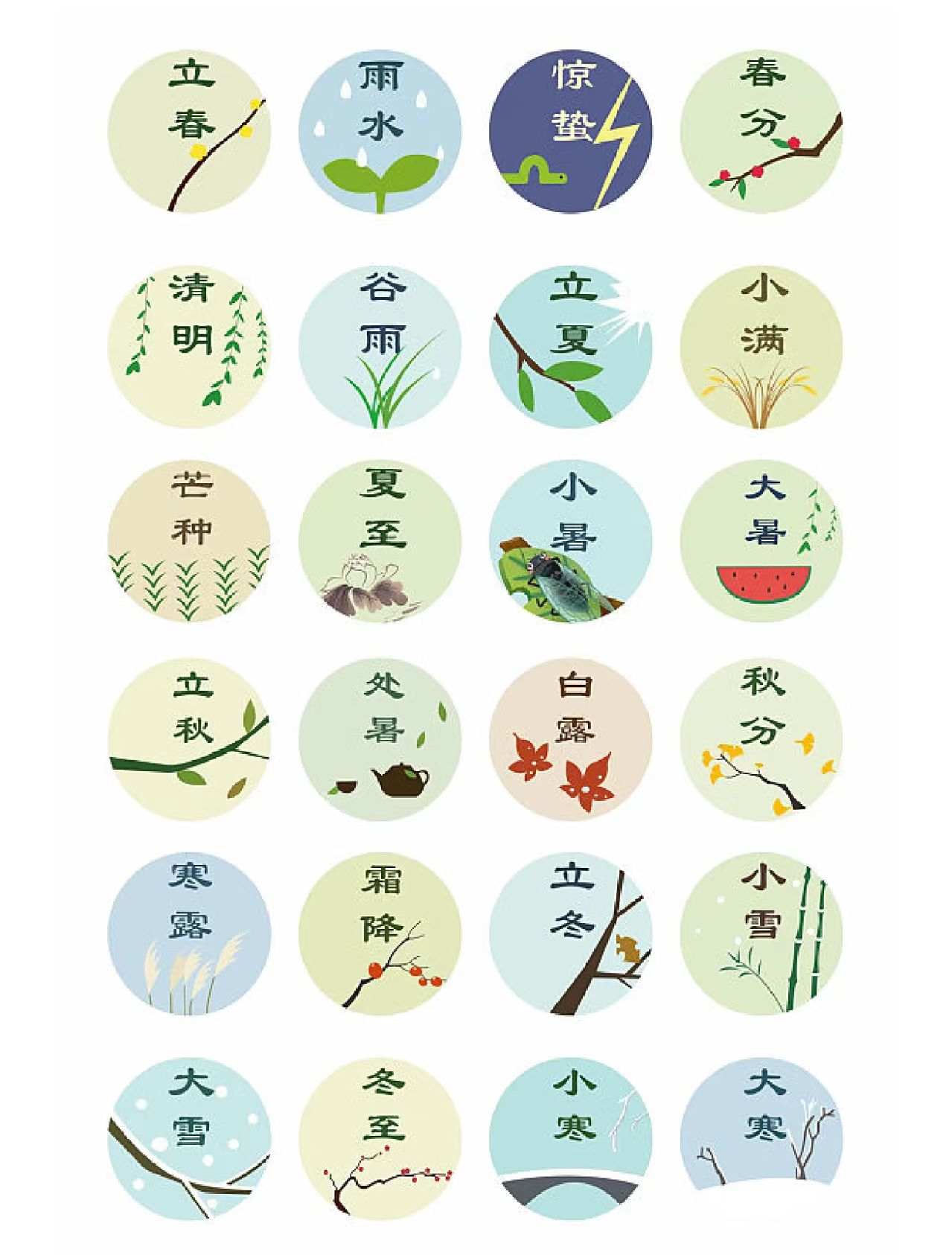

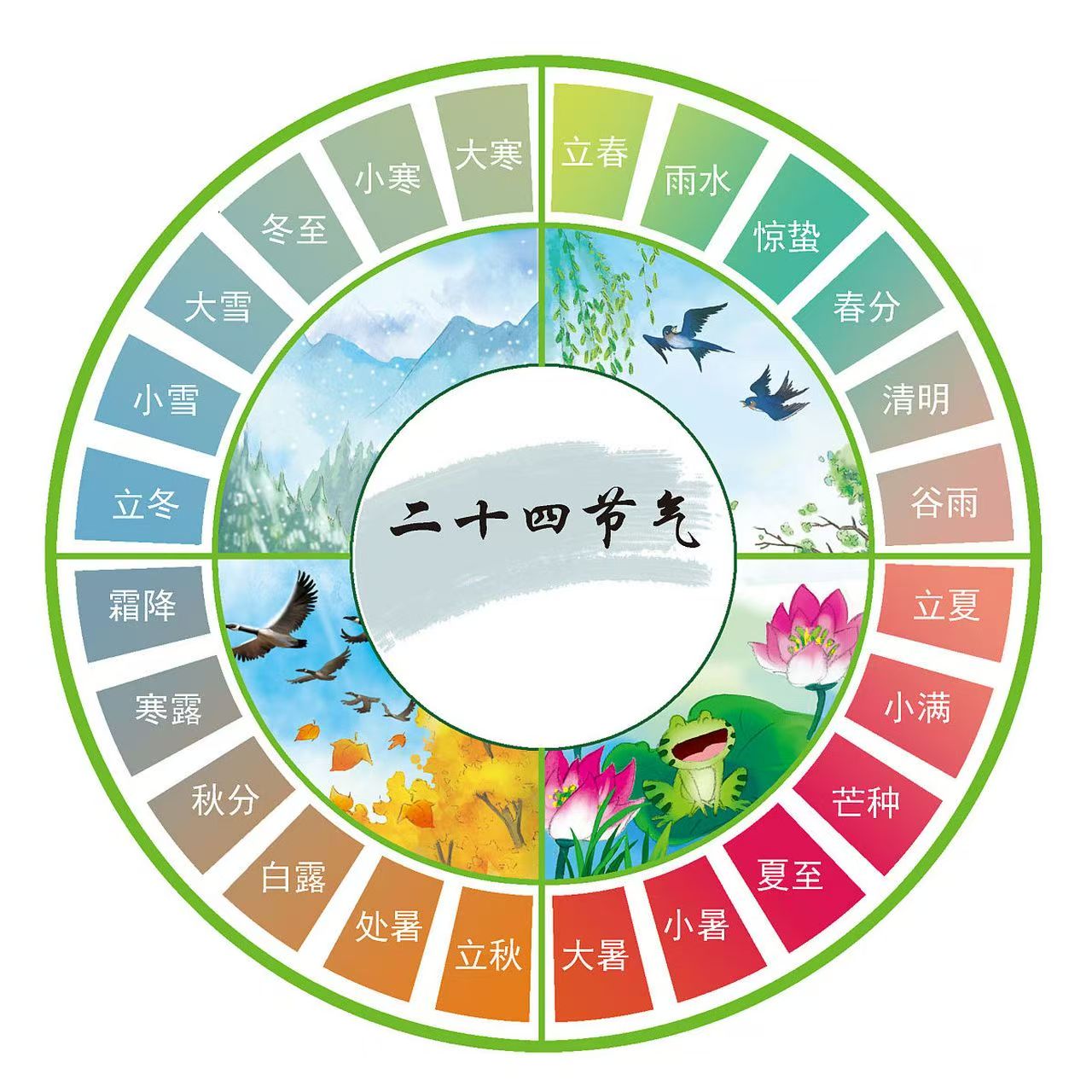

The entire cycle begins not with the burst of spring, but in the quiet depths of winter, with Start of Winter (Lidong) and Minor Snow (Xiaoxue), a time when the world seems to hold its breath. The most significant of these early terms is the Winter Solstice (Dongzhi), which typically falls around December 21st. This day marks the shortest period of daylight and the longest night in the Northern Hemisphere, the nadir of the sun's power. Yet, embedded within this moment of peak darkness is a seed of light, the pivotal turning point where the sun begins its slow return, a concept beautifully captured in the ancient Chinese philosophy of Yin and Yang. It is a time for family gatherings and the consumption of warming foods like dumplings in the north or tangyuan in the south, symbolizing reunion and the nurturing of vitality during the cold. This is followed by Major Cold (Dahan), the absolute pinnacle of winter's chill, a final test of endurance before the wheel turns irrevocably towards renewal.

As the earth continues its orbit, the icy grip of winter gradually loosens, and the air begins to carry a faint, moist promise of change. This is heralded by Start of Spring (Lichun) and Rain Water (Yushui), terms that speak not of immediate warmth, but of the initial, crucial thaw. The snowmelts and the gentle rains begin to nourish the desiccated soil, a vital preparation for the life to come. Then comes Awakening of Insects (Jingzhe), a term brimming with kinetic energy. It signifies the time when the first spring thunderstorms rumble across the land, their vibrations felt deep within the earth, stirring the hibernating creatures from their slumber. It is as if the sky itself is sounding a reveille for all of nature. This period of reawakening culminates in the Vernal Equinox (Chufen), around March 20th, a day of perfect celestial balance when day and night are of equal length. The sun sits directly above the equator, and the world is poised in a moment of exquisite equilibrium, symbolizing balance and fairness in the natural order.

With the balance struck, spring unfolds in all its vibrant glory. Clear and Bright (Qingming), perhaps one of the most poetically named terms, is a day of dual significance. It describes the weather—the skies often become lucid and the air fresh and bright. Culturally, it is the time for the Qingming Festival, a day for families to sweep the tombs of their ancestors, honoring the past while embracing the vibrant life of the present. It is a profound ritual that connects generations, set against a backdrop of burgeoning greenery. This is followed by Grain Rain (Guyu), the final spring term, whose name directly references the life-giving showers that are essential for the early growth of young crops. The farmers, who have watched the heavens and felt the soil, understand that this rain is as precious as grain itself, ensuring the success of the first sowings and the health of the tender shoots now carpeting the fields.

The transition from the gentle warmth of spring to the burgeoning heat of summer is marked by Start of Summer (Lixia). The sun grows stronger, and the days noticeably lengthen. Grain Buds (Xiaoman) describes the pleasing sight of summer grains like wheat becoming plump and heavy, though not yet fully ripe, a stage of potential and promise. Then comes Grain in Ear (Mangzhong), a term that evokes a scene of intense agricultural activity. It is the busiest time for farmers, who must rush to harvest the mature wheat and promptly plant the summer crops like millet. The name itself can be interpreted as "the grain with awn," referring to the bearded husk of barley and wheat, but it is homophonous with a word meaning "busy," perfectly capturing the essence of this frantic and crucial period in the rural calendar.

The sun reaches its zenith during Summer Solstice (Xiazhi), around June 21st, bringing the longest day and the shortest night of the year. This represents the peak of Yang energy, the fiery, active principle in nature. Yet, just as with the winter solstice, this apex contains the seed of its own decline, as the days will now slowly begin to shorten. The heat, however, continues to intensify. Minor Heat (Xiaoshu) and Major Heat (Dashu) are aptly named, describing the sweltering and humid conditions that characterize the core of the Chinese summer. This is a time when growth is rapid and forceful, but the oppressive heat can also be a trial. It is a period for seeking shade, consuming cooling foods like watermelon and mung bean soup, and waiting for the eventual relief that the next cycle will bring.

That relief is first signaled by Start of Autumn (Liqiu), a term that brings a psychological coolness even if the lingering summer heat, known as "Autumn Tiger," persists. The air begins to dry, and the light takes on a softer, golden quality. End of Heat (Chushu) confirms this shift, indicating that the stifling dog days of summer are finally retreating. The temperature drops noticeably, and the world prepares for the harvest. The moisture in the air begins to condense with the cooling temperatures, leading to White Dew (Bailu), a term that paints a picture of delicate dewdrops glistening on morning grass, the first tangible evidence of autumn's crisp touch. This cooling trend deepens with the Autumnal Equinox (Qiufen), another day of balance around September 22nd, mirroring the vernal equinox. Day and night are once again equal, but the momentum is now firmly with the encroaching darkness and coolness.

The later autumn terms are rich with imagery of cold and frost. Cold Dew (Hanlu) indicates a further drop in temperature, with the dew becoming colder, almost on the verge of frost. Then comes Frost's Descent (Shuangjiang), the final term of autumn. This is when the first frost typically appears, a definitive signal from nature that the growing season is over. Farmers must quickly bring in the last of their harvest, such as sweet potatoes and late-ripening fruits, before the frost can damage them. The falling frost acts as a natural painter, transforming the verdant landscape into a tapestry of gold, crimson, and amber as the leaves change color and drop, creating a scene of poignant and majestic beauty.

In contemporary China, the Twenty-Four Solar Terms have transcended their agricultural roots to remain deeply embedded in the cultural psyche. They continue to guide dietary habits, with people eating specific foods believed to harmonize with the body's needs during each term—nourishing and warming foods in winter, light and cooling dishes in summer. They inspire poetry, art, and proverbs, providing a shared cultural vocabulary. Festivals like Qingming and the Winter Solstice are major holidays centered around these terms. Even in bustling modern cities, where the direct connection to farming has been lost for many, the solar terms offer a way to reconnect with the natural world, a reminder of a rhythm that is older and more fundamental than the frantic pace of urban life. They are a living heritage, a bridge between the wisdom of the ancestors and the realities of the present.

The Twenty-Four Solar Terms stand as a profound cultural artifact, a system that seamlessly wove together astronomy, meteorology, agriculture, and social customs into a single, coherent tapestry. It is a testament to a civilization that looked to the heavens not with fear, but with a desire to understand its place within a larger, ordered cosmos. For the outside world, understanding these terms is to understand a fundamental aspect of the Chinese spirit—one that values foresight, respects natural law, and finds beauty and meaning in the eternal, repeating rhythm of the seasons. They are not just a calendar, but a philosophical guide, a poetic language for the passage of time, and a timeless melody composed by the earth and the sky, a melody that continues to resonate through the heart of Chinese culture.