Sunlight filters weakly through the smog, illuminating the peculiar scene unfolding beneath the eaves of Shanghai's People's Park every weekend. Along the pathways, row upon row of umbrellas stand open, shielding not people from rain, but laminated A4 sheets pinned to strings. These sheets, weathered by time and the elements, bear handwritten details seemingly designed for maximum efficiency: "Daughter, Born 1990, 1.65m, Fudan MBA, State-Owned Enterprise Executive," followed by stringent requirements like "Seeking: Male, Born 1985-1988, 1.78m+, Shanghai Hukou, Property Ownership, Overseas Degree Preferred." This vibrant, slightly chaotic spectacle is the city's famed "Marriage Market," a visceral testament to the immense societal pressures surrounding marriage in contemporary China. It represents merely one visible node in the intricate, often bewildering web of modern Chinese matchmaking – a tradition profoundly reshaped by rapid economic ascent, deep-seated cultural expectations, and the relentless tide of technology.

The roots of arranged introductions run deep, intertwined with millennia of Confucian values emphasizing family lineage, social stability, and filial piety. Historically, marriages were strategic alliances between families, orchestrated by professional matchmakers (meipo) who meticulously assessed social standing, economic prospects, and astrological compatibility (bazi). Individual desires were secondary to collective familial duty and continuity. While the social upheavals of the 20th century, superficially attacked these "feudal" practices, the fundamental emphasis on marriage as a cornerstone of adult life and social acceptance endured beneath the surface. Mass urbanization saw millions migrate from villages to booming metropolises, seeking education and unprecedented economic opportunity. This mobility severed traditional kinship networks that once facilitated introductions, creating a vacuum filled by both resurrected traditions and innovative new systems. Simultaneously, China's stringent One-Child Policy, implemented in 1979, concentrated parental hopes, anxieties, and resources onto a single heir. For many urban parents, especially those who weathered periods of scarcity, their child’s marital choice became inextricably linked to their own sense of achievement, legacy, and future security. The pressure wasn't merely about companionship; it was about securing status, economic stability, and ensuring care in old age within a society where state-supported welfare remains limited.

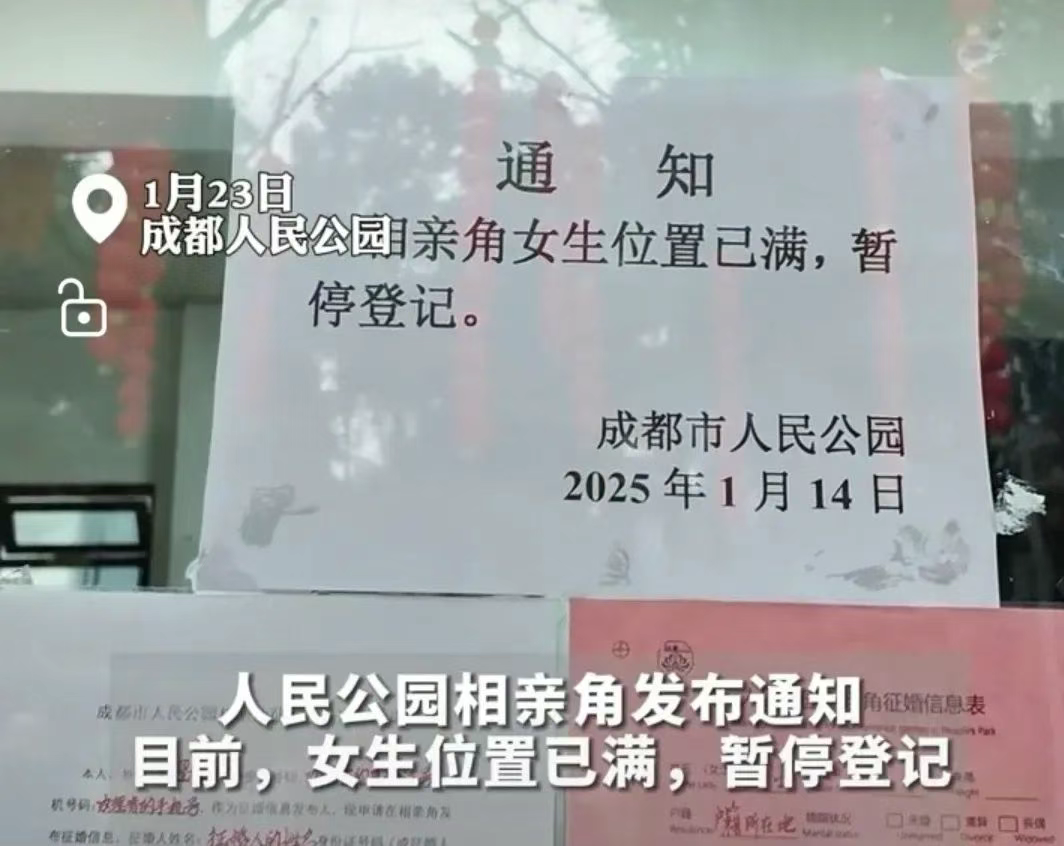

This confluence of fractured social networks, amplified parental investment, and persistent cultural imperatives fuels the intense modern matchmaking phenomenon. The pressure clock starts ticking loudly, particularly for women, upon university graduation. The pervasive term "leftover women" (shengnü), officially propagated in state media around 2007, starkly labels educated, urban women who remain unmarried past their mid-twenties. This societal stigma leverages deep anxieties about declining fertility and the perceived threat of educated women prioritizing careers over traditional family roles. Consequently, parents, especially mothers, often become proactive, even aggressive, agents in their children's search for partners. The Shanghai Marriage Market is their most visible battlefield, but similar parental matchmaking corners exist in parks across major cities like Beijing, Guangzhou, and Chengdu. Armed with their child's resume-like biodata – listing age, height, education, occupation, income, property ownership, and sometimes even blood type or astrological signs – parents scout for suitable matches, engaging in rapid-fire negotiations with other parents. The process is transactional, pragmatic, and often devoid of any input from the individuals whose lives are being bartered. Parents justify their involvement as a necessary service, citing their children's demanding careers, perceived naivety in matters of the heart, or simple lack of time. Many young professionals, working exhaustively long hours in highly competitive environments, do concede that meeting potential partners organically is challenging. Dating apps offer one avenue, but the sheer volume of profiles and concerns about authenticity often lead to fatigue. Professional matchmaking services, ranging from exclusive high-net-worth clubs charging exorbitant fees to online platforms employing AI algorithms, have proliferated, attempting to provide more curated, efficient solutions. Television dating shows like the long-running "If You Are the One" (Fei Cheng Wu Rao) exploded in popularity, offering a voyeuristic glimpse into courtship rituals laced with blunt questions about income, property, and future plans – simultaneously reflecting and reinforcing the materialistic undercurrents of modern matchmaking. These shows highlighted the complex interplay between lingering romantic ideals and the hard-edged economic pragmatism demanded by modern urban life.

Material considerations undeniably form a crucial pillar of the contemporary Chinese matchmaking equation, a reality amplified by skyrocketing living costs, particularly property prices in tier-one cities. The expectation for men to own property before marriage (fangzi) is often non-negotiable for many families, creating a significant barrier to entry. Similarly, a stable, well-paid job, preferably with a state-owned enterprise or a prestigious multinational, ranks highly. For women, youth and physical appearance remain disproportionately emphasized alongside educational attainment. Families scrutinize potential partners not just as individuals, but as economic units whose combined assets, earning potential, and family backgrounds (the concept of mendang hudui – matching social status) can provide security and upward mobility for the new couple and potentially their future children and aging parents. This intense focus on tangible assets frequently overshadows notions of romantic love, emotional compatibility, or shared values in the initial stages of matchmaking orchestrated by families or services. The infamous phrase "I'd rather cry in a BMW than laugh on a bicycle" uttered by a contestant on "If You Are the One" years ago, became emblematic of this stark materialism, triggering national debate about shifting values. Furthermore, China's historical preference for sons, exacerbated by the One-Child Policy and prenatal sex selection, has resulted in a significant demographic imbalance. Estimates suggest tens of millions more men than women of marriageable age exist, creating intense competition among prospective grooms, particularly men from rural areas or with lower socioeconomic status. This "bride shortage" further incentivizes families to emphasize male economic competitiveness (property, income) to secure a desirable match, while paradoxically increasing pressure on women to marry "up" before perceived market value declines. Regional variations also play a crucial role. Matchmaking practices in sprawling, cosmopolitan Shanghai, driven by intense status competition and property value anxieties, differ markedly from those in manufacturing hubs like Dongguan, where pragmatic considerations about shared work ethic and stability might prevail, or in rural villages reliant on local matchmakers navigating complex clan relationships and bride-price (caili) negotiations increasingly strained by the gender imbalance.

Technology promises efficiency and broader horizons, but also introduces new complexities. Dating apps like Momo, Tantan (China's Tinder equivalent), and Zhenai dominate the digital landscape. They offer unprecedented access to potential partners beyond immediate social circles, theoretically allowing individuals to bypass parental gatekeepers. Algorithms claim to match based on interests, location, and preferences. Yet, the digital realm often reproduces, and sometimes amplifies, existing societal pressures and biases. Profiles become hyper-optimized advertisements, emphasizing career achievements, property ownership, and carefully curated photos. The sheer volume can be paralyzing, encouraging a "shopping" mentality where genuine connection is hard to foster amidst endless swiping. Concerns about deception – from minor exaggerations to elaborate financial scams – are rampant, fostering a climate of initial skepticism. The convenience of apps also risks commodifying relationships further, reducing the search for a life partner to a series of rapid, superficial evaluations. While some successful relationships undoubtedly blossom online, many young people report feeling disillusioned by the impersonal nature and the pressure of constant presentation. Interestingly, technology has also empowered parental involvement in new ways. Parents adeptly use social media groups (like WeChat groups dedicated to matchmaking) and online platforms specifically designed for them to post their children's profiles and vet potential candidates, extending their reach far beyond the local park. The digital and analog worlds of matchmaking increasingly collide and overlap.

Despite the pervasive pressures – familial, societal, economic – resistance and subtle shifts are discernible, particularly among the younger, urban educated cohorts. A growing number articulate a desire to prioritize personal fulfillment, career ambitions, and genuine emotional connection over societal timetables or purely pragmatic calculations. They seek partners who share their values, interests, and vision for life, rather than merely fulfilling a checklist devised by others. The rising age of first marriage in major cities reflects this pushback against the "leftover" narrative. More individuals, especially women, are choosing to remain single rather than enter unsatisfying unions, embracing financial independence and alternative lifestyles. Cohabitation, while still less common and sometimes fraught with familial disapproval, is increasing. Divorce rates, once exceedingly low, have risen, signaling a decreasing tolerance for unhappy marriages. Furthermore, a discourse advocating "companionate marriage" focused on mutual respect, shared interests, and emotional intimacy is gaining traction, challenging the older model centered purely on social duty and economic stability. This doesn't signify a wholesale rejection of parental input or practical considerations; rather, it reflects a desire for greater agency and balance. Young people navigating the matchmaking landscape often engage in complex negotiations – appeasing anxious parents by meeting prospects sourced through traditional channels while simultaneously pursuing their own connections through friends or apps, hoping to find someone acceptable to all parties, themselves included. The friction arises when deeply held personal desires clash with equally deep-seated filial obligations and societal expectations.

The quest for partnership in modern China unfolds within a unique crucible where ancient traditions collide with breakneck modernity, collective duty grapples with individual aspiration, and romantic ideals are constantly weighed against harsh socioeconomic realities. The sight of parents anxiously touting their children's resumes in a public park is not merely a quaint cultural curiosity; it is a vivid tableau of profound societal anxieties about stability, continuity, and navigating an uncertain future. It speaks to the immense weight of filial piety, the fierce competition for resources and status in a rapidly evolving society, and the enduring belief that marriage remains the fundamental bedrock of adult life and social acceptance. While technology offers new tools and pathways, it rarely simplifies the core human dilemma of finding connection. The future of Chinese matchmaking likely lies not in the disappearance of parental involvement or pragmatic considerations, but in a gradual, contested evolution towards a model that allows greater space for individual choice and emotional fulfillment within the enduring framework of family and societal expectations. The laminated sheets in the park may eventually fade, but the complex navigation of hearts, family duty, and economic survival will continue to shape the pursuit of love and partnership in China for generations to come, a testament to a society striving to reconcile its past with an ever-changing present. The journey towards finding a partner remains a deeply personal odyssey, yet one profoundly illuminated by the societal forces that shape every step.