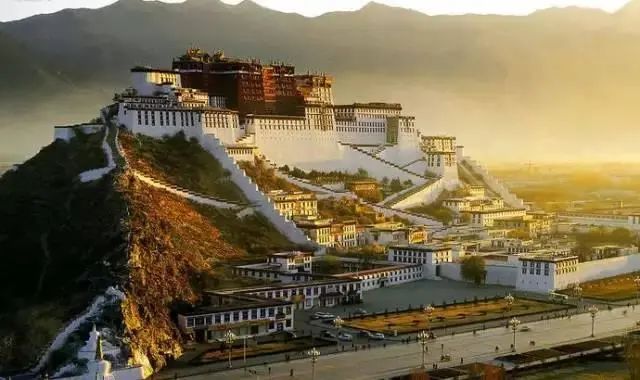

Perched high upon Marpo Ri, the "Red Hill," overlooking the ancient city of Lhasa, the Potala Palace commands the landscape with an aura of profound spirituality and majestic grandeur. This awe-inspiring complex, a UNESCO World Heritage Site and arguably the most iconic symbol of Tibet, transcends mere architecture. It is a living testament to centuries of Tibetan Buddhism, a repository of unparalleled cultural treasures, and a beacon drawing pilgrims and travelers from across the globe. Its stark white and deep crimson walls, crowned with gleaming golden roofs, rise dramatically against the vast backdrop of the Himalayan sky, embodying the unique fusion of earthly power and sacred devotion that defines its history.

The palace's origins stretch back into the mists of the 7th century. King Songtsen Gampo, a pivotal figure in Tibetan history credited with unifying the region and introducing Buddhism, is believed to have constructed a fortress on this strategic hilltop around 637 AD. Legends recount that he built it to welcome his bride, Princess Wencheng of the Tang Dynasty. This early structure, known as the Red Palace, served as a royal residence and a center of governance. Although little remains of this original edifice, its location established the sacred significance of Marpo Ri. The palace derived its evocative name, "Potala," from Mount Potalaka, the mythical abode of Avalokiteshvara (Chenrezig), the Bodhisattva of Compassion, who is revered as the protector deity of Tibet and whose spirit is believed to reside within the Dalai Lamas.

For centuries, the original palace stood, witnessing the ebb and flow of Tibetan dynasties and the deepening roots of Buddhism. However, its modern incarnation truly began in the 17th century under the visionary leadership of the Fifth Dalai Lama, Ngawang Lobsang Gyatso. Following his ascension as the spiritual and temporal ruler of Tibet, he recognized the need for a symbolic seat of power that would reflect the Gelugpa school's dominance and unify the Tibetan people. In 1645, he initiated the monumental task of rebuilding and vastly expanding the Potala Palace upon the ruins of Songtsen Gampo's fortress. This ambitious project consumed decades, continuing long after the Fifth Dalai Lama's passing in 1682 (his death was concealed for 15 years to ensure the palace's completion). The Thirteenth Dalai Lama further expanded and renovated the palace in the early 20th century, adding new chapels and refurbishing older sections, solidifying the structure that stands today.

The resulting edifice is a breathtaking feat of traditional Tibetan architecture, perfectly adapted to its challenging environment. Soaring over 117 meters (384 feet) high and stretching approximately 400 meters (1,300 feet) east-west, the palace dominates the Lhasa valley. Its sheer scale is staggering, comprising over 1,000 rooms, 10,000 shrines, and approximately 200,000 statues, spread across thirteen stories. The design is not merely functional but profoundly symbolic, conceived as a three-dimensional cosmic mandala representing the Buddhist universe. The palace divides distinctly into two primary sections: the outer White Palace (Potrang Karpo) and the inner Red Palace (Potrang Marpo), their colors rich with meaning.

The White Palace forms the secular heart of the complex. Its luminous, thick walls, traditionally whitewashed with lime mixed with milk, symbolize peace and serenity. This section served as the winter residence and administrative headquarters for successive Dalai Lamas and the Tibetan government. Within its labyrinthine corridors and chambers lay the living quarters of the Dalai Lama, including his private apartments and audience halls where he conferred with ministers and received dignitaries. Grand ceremonial halls hosted state functions, while extensive libraries housed invaluable scriptures and records. The vast eastern courtyard, known as Deyangshar, served as a venue for religious dances and festive gatherings. The White Palace exemplifies the integration of governance and spirituality under the unique Tibetan theocratic system.

Contrasting sharply, the Red Palace is the sacred core, radiating an atmosphere of deep devotion. Its striking dark crimson walls, colored with a mixture of red ocher, signify the solemnity and power of religious authority dedicated to the fierce protective deities. This section is wholly devoted to prayer, ritual, and commemoration. It houses the intricate stupa-tombs of eight Dalai Lamas, including the awe-inspiring gold-and-jewel encrusted stupas of the Fifth and Thirteenth Dalai Lamas – masterpieces of Tibetan craftsmanship utilizing staggering quantities of precious metals and stones. Numerous chapels and meditation caves honeycomb the Red Palace. Sacred spaces like the Saint's Chapel (Sasum Lhakhang), believed to contain the original seventh-century meditation cave of King Songtsen Gampo, and the Dharmapala Chapel dedicated to wrathful protectors, pulse with centuries of accumulated prayer. The most sacred chapel, the Phakpa Lhakhang, shelters a revered statue of Avalokiteshvara, a spiritual anchor for countless pilgrims. The walls throughout the Red Palace are adorned with vibrant, intricate murals depicting Buddhist deities, mandalas, historical events like the life of the Fifth Dalai Lama, and legendary tales, forming one of the world's most significant collections of Tibetan religious art.

Constructed primarily from stone, wood, and earth, the Potala Palace showcases remarkable engineering prowess. Its massive stone walls, sloping dramatically inwards for stability, are built without modern foundations, relying instead on deep rocks and compacted earth. Traditional wooden beams and rafters, carved with intricate motifs, support the floors and ceilings. The iconic golden roofs, gleaming brilliantly under the intense Tibetan sun, are adorned with intricate symbols such as the golden dharma wheels flanked by deer, representing the Buddha's first sermon, and victory banners. Copper, heavily gilded with pure gold, covers these roofs, designed to withstand the harsh, high-altitude climate with its intense UV radiation, extreme temperature fluctuations, and arid conditions. The entire structure incorporates sophisticated systems for drainage and ventilation, demonstrating an ancient understanding of sustainable building practices in a demanding environment. The absence of modern machinery during its construction makes its sheer scale and precision even more astounding; materials were transported manually, often carried up the steep hill paths by porters or hauled with ropes.

For centuries, the Potala Palace was the vibrant epicenter of Tibetan life. It served as the winter residence for the Dalai Lamas, the seat of the Tibetan government (Ganden Phodrang), a major monastic institution housing thousands of monks, and the focal point for major religious festivals. The daily rhythm within its walls was governed by prayer, study, and ritual. Monks chanted scriptures in resonant unison, butter lamps flickered before countless sacred images filling the air with their distinctive scent, and pilgrims prostrated themselves in reverence, generating an atmosphere thick with devotion. The palace witnessed coronations, political councils, profound philosophical debates, and the solemn ceremonies surrounding the passing and reincarnation of the Dalai Lamas. It was, in every sense, the pulsating heart of Tibet.

The tumultuous events of the 20th century inevitably impacted the Potala Palace. Following the Dalai Lama's departure from Tibet in 1959, the palace ceased to function as an active residence or governmental center. During the Cultural Revolution (1966-1976), like many religious sites across China, it faced significant threats. While the main structure survived largely intact due to its immense symbolic and architectural importance, many precious artifacts within were destroyed or looted, and some monastic structures surrounding the palace were damaged. Recognizing its universal value, UNESCO inscribed the Potala Palace on the World Heritage List in 1994, extending the designation in 2000 and 2001 to include the adjacent Jokhang Temple and Norbulingka palace.

Today, the palace stands primarily as a state-run museum and a profoundly significant religious site. While no longer a political capital or the residence of the Dalai Lama, it remains an active place of pilgrimage and worship. Devotees from across Tibet and beyond continue to circumambulate its sacred paths, spin prayer wheels embedded in its walls, and prostrate themselves at its gates, maintaining a tangible connection to its spiritual essence. For international visitors, it offers an unparalleled glimpse into Tibetan history, art, and religious practice. Guided tours wind through select halls, chapels, and tombs, showcasing breathtaking murals, intricate statues, and the dazzling splendor of the funerary stupas.

Preserving this colossal, ancient structure perched on a hilltop in an earthquake-prone zone under extreme weather conditions is a monumental ongoing challenge. Constant vigilance and meticulous restoration work are required to combat the effects of weathering, aging materials, and seismic activity. Chinese authorities, in collaboration with international conservation experts, undertake extensive projects focusing on structural reinforcement, mural restoration, artifact conservation, and environmental monitoring. Balancing the demands of tourism – providing access to hundreds of thousands of visitors annually – with the imperative of preserving the fragile artwork, architecture, and spiritual atmosphere presents a constant dilemma. Visitor numbers are regulated, and strict protocols govern behavior within the sacred spaces.

The Potala Palace is far more than a collection of buildings; it is a powerful symbol deeply embedded in the Tibetan consciousness and admired worldwide. It embodies the resilience of Tibetan culture and Buddhist faith through centuries of change and challenge. Its imposing silhouette against the vast Tibetan plateau evokes a sense of timelessness and spiritual aspiration. It speaks of artistic genius, profound devotion, and the unique historical trajectory of the Tibetan people. As one of humanity's most extraordinary cultural achievements, it serves as a vital bridge connecting the past to the present, the sacred to the historical, and invites all who encounter it, whether pilgrim or visitor, to contemplate the depths of human faith and artistic endeavor. Standing sentinel over Lhasa, the Potala Palace remains an enduring pinnacle of devotion, its white and red walls whispering tales of kings and lamas, prayers and politics, tragedy and endurance, forever etched into the roof of the world.