China, with its rich historical and cultural heritage, is home to a vast range of intangible cultural heritage (ICH), including traditional craftsmanship, performing arts, festive events, and oral traditions. These ICH elements not only represent the diverse cultural identity of China’s various ethnic groups but also embody the collective wisdom and continuity of communities passed down through generations. As the country actively works to safeguard its ICH through legal and policy measures, it faces significant challenges in protecting the intellectual property (IP) rights associated with these traditions.

While China has ratified the UNESCO Convention for the Safeguarding of the Intangible Cultural Heritage (2003), which has helped bolster protective efforts, the unique characteristics of ICH make it difficult to apply traditional IP laws. This article will explore the IP protection challenges facing China's ICH, provide examples to illustrate these issues, and suggest ways to address these concerns.

I. Unique Characteristics of ICH and IP Protection

ICH differs from tangible cultural assets in its intangible nature, being primarily based on oral traditions, cultural practices, and community-held skills. Protecting the IP associated with ICH presents several unique challenges:

1. Collective Ownership: Many forms of ICH are owned by specific communities rather than individuals, which contrasts sharply with the individual or corporate ownership that traditional IP law favors.

2. Cultural and Commercial Intersection: ICH not only carries cultural significance but also often holds commercial value, such as traditional handicrafts or performances. Balancing the protection of cultural integrity with the potential for commercial exploitation is a delicate task.

3. Oral and Non-Written Transmission: ICH is often transmitted orally or through practice, without formal documentation. This can create difficulties in proving ownership or establishing prior art when IP disputes arise.

II. Major Challenges in Protecting China’s ICH Under IP Law

1. Inadequate Legal Framework

China’s current IP laws focus primarily on patents, trademarks, and copyrights, which are ill-suited to accommodate the distinctive nature of ICH. Many ICH elements lack the innovative characteristics or the fixed, tangible forms that traditional IP law requires for protection.

For example, “Jingtailan” (Cloisonné craftsmanship), a traditional Beijing art form, involves intricate metalworking techniques passed down over centuries. While cloisonné designs could theoretically be protected under trademark or copyright laws, the techniques themselves are difficult to protect via patent, as they have been collectively developed and refined by generations of artisans over time. The communal nature of this craft complicates the ownership of the intellectual property rights, leaving the community vulnerable to unauthorized exploitation by commercial entities.

Additionally, traditional performing arts like “Kunqu Opera”, one of China's oldest operatic forms, are only partially covered by copyright law. Copyright can protect specific performances or adaptations, but it does not address the broader cultural and artistic traditions that form the core of this art, such as oral transmission, community involvement, and improvisation.

2. Ambiguity in Rights Ownership and Representation

The collective ownership of many ICH elements clashes with the individual-centric nature of traditional IP regimes. Establishing ownership for a community-based ICH can be highly complex. For instance, the “Grand Song of the Dong Ethnic Group”, a multi-part polyphonic music tradition from the Dong ethnic group in southern China, is collectively owned and performed by the community. If a commercial entity or individual outside the community seeks to capitalize on this cultural asset, it becomes unclear who within the Dong community can represent the group’s collective interest and claim the rights to the music.

Moreover, many ICH communities are unaware of the existing IP protection tools or lack the resources to navigate complex legal processes. In some cases, even if a community is aware, its members may not agree on how to manage and enforce IP rights.

3. Cultural Appropriation and Uncontrolled Commercialization

Another significant challenge is the commercialization and misappropriation of ICH. As ICH becomes more popular in tourism, fashion, and entertainment, there is a growing risk of cultural appropriation, where elements of a culture are taken out of context or misrepresented for profit without proper acknowledgment or benefit to the originating community.

For instance, the traditional Tibetan art of Thangka painting, a form of religious scroll painting, has faced widespread commercialization. Many Thangka artworks are now mass-produced in factories, stripping the practice of its original spiritual and cultural significance. Local Tibetan artisans, who traditionally create Thangka as part of religious rituals, often do not benefit from the profits generated by these commercial reproductions. This not only dilutes the cultural value of the artwork but also exploits the labor and cultural heritage of the Tibetan community.

Another example is the “Water Splashing Festival” of the Dai ethnic group, celebrated in Yunnan. Originally a religious and cultural festival, it has been extensively commercialized for tourism purposes. While it attracts thousands of visitors, the cultural essence of the event is increasingly overshadowed by its commercial aspects. The local Dai community sees little economic return from the commercialization, nor does it have control over how the festival is presented to outsiders.

4. Challenges in the Digital Age

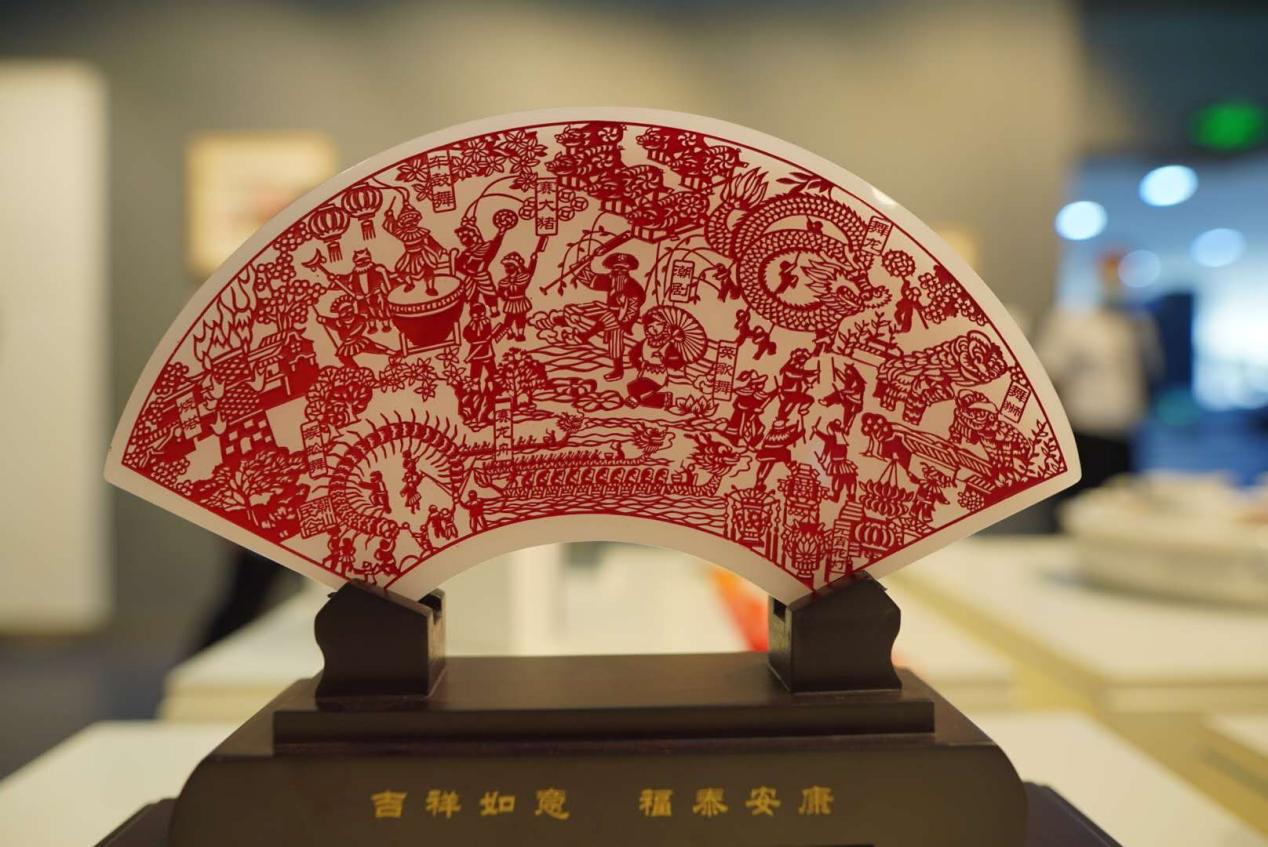

The rise of the internet and digital technologies has introduced new complexities to ICH protection. While the digital era offers unprecedented opportunities to promote ICH, it also makes ICH more vulnerable to unauthorized use and copying. Traditional forms of art like paper cutting, shadow puppetry, and Chinese folk music are now widely available online. Their digital dissemination, often without proper licensing or acknowledgment, increases the risk of misappropriation.

In many cases, videos, images, or audio recordings of ICH performances are uploaded to the internet without the consent of the originating community. Once these cultural assets enter the digital realm, they can be easily copied and modified, making it challenging to control their use or to enforce rights over them. For example, folk music from China’s ethnic minorities, such as the Guizhou Miao's traditional songs, have been recorded and shared online without any revenue or recognition going back to the community.

5. Conflict Between Cultural Values and Modern IP Systems

Many Chinese ICH elements embody cultural values that conflict with the principles of modern IP law. Traditional Chinese medicine (TCM), for instance, is a significant part of China’s ICH. TCM techniques and knowledge have been passed down through oral tradition and practice rather than documented as formal intellectual property. However, modern IP laws require clear ownership, novelty, and originality to grant protection.

For example, a traditional herbal remedy might not qualify for patent protection because it has been known and used for centuries, even though it holds great value. This puts traditional knowledge at risk of being appropriated by pharmaceutical companies, who may isolate specific compounds and seek patents, while the communities that developed the original remedy receive no compensation or recognition.

III. Solutions and Strategies for Better Protecting China's ICH

1. Establish a Legal Framework Specifically for ICH

China should consider developing a legal framework that specifically addresses the protection of ICH, reflecting its unique characteristics. Laws that clearly recognize collective ownership, dynamic transmission, and the cultural significance of ICH are essential to safeguard these traditions effectively. For example, introducing Traditional Knowledge Protection Laws could provide the legal means to protect practices like Miao silver crafting or Lacquerware artistry.

Moreover, establishing guidelines on how benefits from the commercialization of ICH should be shared with local communities would help ensure that ICH bearers are properly compensated.

2. Strengthen Community Awareness and Involvement

Educating ICH communities about IP protection and providing them with the resources to protect their cultural heritage is vital. Governments and NGOs can play a key role by offering training on IP laws, patent application processes, and commercial negotiations. Communities should be empowered to manage their IP rights and negotiate fair terms when their culture is used in commercial endeavors.

For instance, efforts to protect the Batik art of the Miao ethnic group in Guizhou could include educating local artisans about the benefits of registering trademarks for their designs. This would help them prevent unauthorized copying and commercial exploitation.

3. Encourage Responsible Commercialization

Commercialization of ICH can be beneficial if done ethically and responsibly. Governments and businesses should work together to ensure that ICH commercialization respects the cultural context and provides economic benefits to the originating communities. For example, fair-trade initiatives could be established to promote Tibetan handicrafts or Chinese shadow puppetry while ensuring that the artisans receive fair compensation for their work.

4. Develop Digital Protection Mechanisms

As ICH increasingly moves into the digital realm, developing robust mechanisms to protect ICH from misappropriation online is crucial. Digital rights management (DRM) tools and licensing platforms can be used to ensure that ICH content shared online is properly credited and that any financial benefits flow back to the originating communities. Governments can work with tech companies to develop ICH-specific copyright protections.

5. Foster International Cooperation

Given the global nature of IP and the growing international interest in ICH, China should continue to foster international cooperation in ICH protection. Establishing agreements with other countries on how to handle the protection and commercialization of shared cultural heritage can help reduce cases of cross-border appropriation.

Conclusion

The challenges associated with protecting the intellectual property of China’s intangible cultural heritage are complex and multifaceted. Legal frameworks need to evolve to recognize the collective and evolving nature of ICH. By strengthening legal protections, raising awareness within ICH communities, encouraging responsible commercialization, and developing digital tools, China can better safeguard its rich cultural heritage for future generations while ensuring that local communities benefit economically and culturally.